If you’ve been looking at solar panels, solar batteries, and whatever your utility company is calling your plan this week, you’ve probably noticed two things:

- Everyone promises massive cost savings and lower electricity bills.

- Almost nobody explains how a solar panel system (or solar PV system) interacts with tariffs, exports, and your real-world energy usage.

This is a practical field guide for Australian homeowners who want to make smart choices about a solar power system, solar battery storage, and the “fine print” stuff that decides whether you get energy savings… or just a significant investment you regret.

Solar basics that actually matter (so you don’t buy the wrong system)

A home solar panel system is pretty simple in concept: solar panels on the roof turn sunlight into electricity, and you use that power in the house first.

Anything you don’t use at the time becomes excess solar energy (also called excess energy / excess power) and may be exported to the electricity grid (your power grid).

1) DC vs AC: the one conversion that drives everything

Solar panels generate direct current (DC). Your house runs on AC (alternating current), so you need an inverter to convert it. DC is also what charges and discharges solar batteries (your energy storage).

2) Think in “when you use power,” not “how many panels fit”

Solar is best when it replaces expensive grid electricity you would’ve bought anyway.

- If you use more power during the day (WFH (work from home), air con, pool pump, dishwasher, laundry), you’ll self-consume more solar.

- If you use most power after sunset, you’ll export more and buy more from the grid later—unless a battery shifts that energy to later use.

So system sizing should start with your real energy usage and energy needs, not the biggest solar array you can squeeze onto the roof.

The Clean Energy Council’s consumer guidance makes the same point: match system size to consumption patterns instead of assuming “bigger is better.”

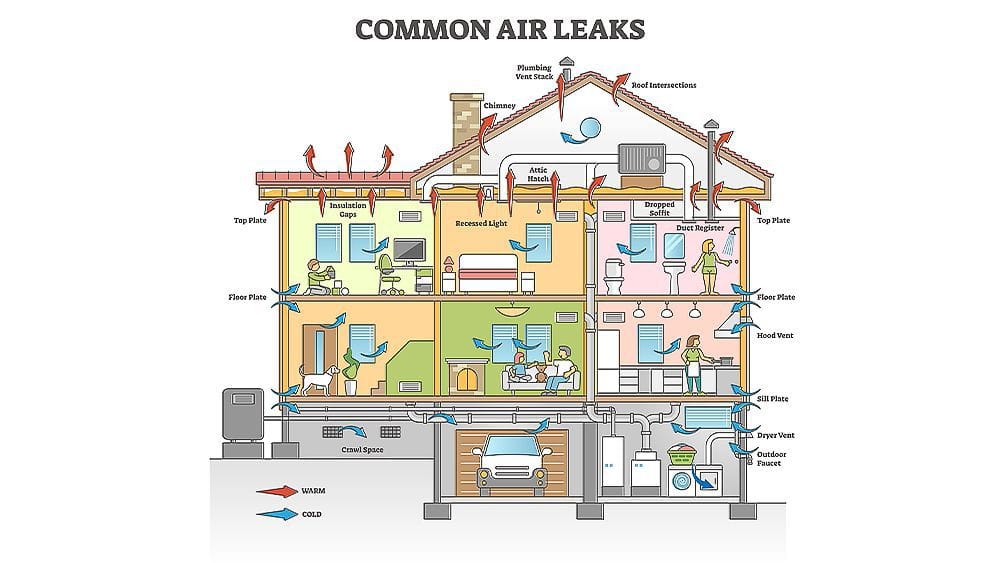

3) Roof reality: shade and layout beat “premium panels” most days

Before you obsess over brand-name solar modules, get these sorted:

- Shade (trees, chimneys, two-storey neighbours) can wreck energy production on a whole string if the design is lazy.

- Orientation and tilt affect production timing (morning vs afternoon output), which matters if you’re trying to run appliances during certain windows.

- Split arrays (east/west) can be a smart move if your household load is spread across the day.

This is where good design beats marketing. A slightly “less fancy” panel on a better roof layout often delivers more usable energy.

4) Monitoring—it’s how you catch problems early

A decent monitoring system helps you spot drops in output, inverter faults, or a string not performing. If you’re aiming for energy savings, you need visibility. “Set and forget” is how you end up paying bills for months before noticing the system isn’t doing what you paid for.

5) Grid connection rules and inverter settings matter in Australia

Australia has connection requirements and inverter settings standards designed to keep the grid stable, and non-compliant settings can cause headaches (including performance limits).

You don’t need to memorise standards—but you do want an installer who commissions properly and can show you what’s been set up.

6) Quote hygiene: what you should demand in writing

When comparing quotes for a new solar system, ask for:

- Panel and inverter model numbers (not “Tier 1 panels” as a vibe)

- Layout (where panels go) and any shade assessment

- Expected production estimate (and the assumptions)

- Any switchboard work, metering, or electrical wiring upgrades included (or excluded)

- Warranty terms and who actually services them (installer vs manufacturer)

Also note: in Australia, a lot of pricing includes an STC-based discount applied upfront by the retailer/installer (it should be shown clearly).

Pull your last 12 months of bills (or smart meter data if you have it) and write down when your household uses the most electricity. That one step makes every later choice—system size, tariff fit, and whether batteries make sense—far easier.

Tariffs explained

When Australians say “tariffs,” they usually mean how your electricity bill is priced. It’s not just one number. Most bills have:

1) Supply charge + usage charges

- Supply charge (daily fixed fee): you pay it even if you use zero power.

- Usage (c/kWh): what you pay for each unit of energy you pull from the grid (your grid electricity).

2) The main tariff types you’ll run into

Flat rate

One usage price all day. Easy. Not always best if your usage spikes at certain times.

Time-of-use electricity rates (TOU)

Different prices at different times (peak / shoulder / off-peak). Your bill rises if you use a lot during peak, and drops if you can shift load to off-peak hours.

Demand tariffs

You pay based on your highest short “spike” of usage during certain periods (often measured in 30-minute blocks with a smart meter). One ugly spike (e.g., oven + AC + EV charger) can lift the bill.

Controlled load

A separate cheaper rate for specific appliances (often electric hot water, slab heating, pool heating), usually run in off-peak windows.

Feed-in tariffs (FiT)

This is the credit you get when your solar panel system exports excess solar energy to the electricity grid. Rates vary by retailer and state and show up as a credit on your bill.

3) Why solar changes which tariff is “best”

The goal becomes using your solar first (self-consumption) because the savings from avoiding grid power are often bigger than what you earn exporting excess energy.

A solar battery system can then store daytime solar for later use, which can help on TOU plans (avoid peak) and sometimes reduce demand spikes—depending on how it’s configured.

How solar + battery interacts with tariffs (and where you accidentally lose money)

Tariffs decide what your solar is worth at different times of day. Solar and solar batteries decide when you use your own power versus buying grid electricity or exporting excess solar energy.

The basic rule

- If the value of avoiding grid power (your import rate) is higher than what you get paid for exporting (your feed-in credit), you generally want to use more solar in the house first. That’s why tariffs matter so much for cost savings and lower energy bills.

Best-case setup (simple)

You use a decent chunk of electricity during the day, so solar directly covers energy usage like air con, laundry, cooking, pumps, and home office loads. Any leftover becomes excess energy and may export. You get savings because you’re avoiding retail-priced grid imports.

Worst-case setup (also common)

You’re on a plan where peak pricing is high in the evening (time-of-use electricity rates), but your household mostly uses power after sunset. Solar exports all day at a relatively low credit, then you buy back expensive grid power at night.

This is where a battery might help: it stores daytime solar as stored energy and supplies it for later use, reducing what you buy during peak periods.

Batteries don’t magically fix every tariff

A solar battery system helps most when it’s doing one (or more) of these jobs:

- Shifting solar to evenings on TOU plans (avoid peak imports)

- Covering short spikes that might trigger demand-style charges (depends on your setup and limits)

- Providing backup power for essential appliances during a power outage (only if configured for backup)

But a battery won’t fix:

- High daily supply charges

- A household that runs big loads all at once (you’ll still pull hard from the grid if the battery/inverter can’t cover it)

- Bad plan choice or mismatched energy needs

Should I change my plan?

If you have a smart meter, you can compare plans and see how TOU vs single-rate might land based on your usage profile. Energy Made Easy explicitly supports estimating costs for TOU plans and can include solar feed-in credits where available.

Where Virtual Power Plants fit (quickly)

A virtual power plant can add extra value to home battery storage systems by coordinating exports or battery use, but the benefit depends on the program rules and your retailer/network conditions—so treat it as “possible upside,” not guaranteed payback.

Before you buy more hardware, identify (1) your current tariff type (single-rate vs TOU, etc.), and (2) when you buy the most grid electricity.

That tells you whether you need behaviour changes, a plan change, more solar, or battery shifting.

New builds vs existing homes (how to avoid paying twice)

Solar and batteries work on both new and existing homes — but new builds let you plan the “boring stuff” up front (switchboard space, conduits, roof layout), which can reduce additional costs and make upgrades cleaner later.

New builds: bake it in while the walls are open

If you’re building, treat your solar panel system and future solar batteries like any other core service — not a bolt-on.

What to plan early:

- Roof design for energy production: leave clear, shade-free roof area for a decent solar array (avoid breaking the best roof faces up with vents/skylights where possible). The Clean Energy Council’s consumer solar guide stresses doing your homework on system design and installation, not just shopping on price.

- Switchboard capacity + layout: allow space for solar protection gear, metering requirements, and battery-ready wiring. (This is where retrofits often get messy and expensive.)

- Conduits and cable paths: run sensible conduits now so you’re not paying later for ugly external trunking or long cable runs. This matters for electrical wiring, install time, and labour costs.

- Battery location and available space: decide where home batteries could live (garage wall, external enclosure, etc.) and keep access clear. Battery installs also need to meet Australian requirements and safety standards expectations; the Clean Energy Council battery guide points home owners toward compliant installations and accredited designers/installers.

- Pick listed equipment: for inverters and batteries, Australia has approved product lists and guidance for consumers.

Monitoring system planning: ask for a monitoring system that shows solar production, household consumption, and battery charge/discharge (if installed). It’s much easier to wire and commission neatly at build time.

Even if you don’t buy batteries now, design the home so adding solar battery storage later doesn’t turn into a switchboard rebuild.

Existing homes: start with a reality check (then design around it)

Retrofits can be great — they just have more unknowns.

Common retrofit cost drivers:

- Old or full switchboards: upgrades can add to the total cost fast (and can delay install).

- Long cable runs / tricky access: roof access, tile type, two-storey runs, tight ceiling spaces = higher labor costs.

- Shading and roof constraints: you might need a different panel layout or inverter approach to get decent energy production.

- Backup power expectations: if you want battery backup for a power outage, confirm your chosen solar battery system is configured for backup operation (it’s not automatic in every setup).

Also, if a retailer/installer is talking incentives: in Australia, solar discounts are commonly handled via STCs under the Small-scale Renewable Energy Scheme (not a “federal tax credit” style approach you might hear about in the United States).

Get your switchboard and roof constraints assessed before you compare quotes — otherwise you’re comparing fantasy pricing.

Recommendations by home owner type

These aren’t “one-size-fits-all” rules. They’re starting points based on your energy usage, your tariff, and what you’re trying to achieve.

1) Daytime-at-home households (WFH, kids, daytime AC)

Typical pattern: you use much electricity while the sun is out, so solar gets used directly by home appliances.

Usually works well: a well-sized solar PV system / solar power system first. Batteries can be optional.

Why: you’re already turning solar into immediate energy savings by avoiding grid electricity.

Next move: add a battery only if you still export a lot of excess solar energy, or if you want backup power. (Backup must be configured—it's not automatic.)

2) Evenings-heavy households (out all day, big after-dark load)

Typical pattern: solar produces excess energy in the day, then you buy from the grid at night.

Usually works well: solar + solar battery storage (or at least “battery-ready” design).

Why: a solar battery system can store daytime output as stored energy for later use, which helps when your usage is mostly after sunset.

Tariff note: if you’re on time-of-use electricity rates, this combo often performs better because the battery can reduce peak imports.

3) Backup-focused households (blackouts, medical needs, “keep essentials running”)

Typical pattern: you care about energy security more than payback.

Usually works well: a battery system designed explicitly for battery backup of essential appliances.

Non-negotiable: confirm in writing that the battery is configured to provide backup during a power outage—many systems won’t unless set up for it (anti-islanding shuts solar-only systems down during outages).

Next move: size the kWh battery around essentials + desired runtime (not “whole home” fantasies).

4) EV owners (or “EV soon” households)

Typical pattern: you’ll add a large new load (charging).

Usually works well: solar sized with daytime charging in mind first; battery second.

Why: charging an electric vehicle from daytime solar is often simpler than buying a bigger battery just to charge the EV overnight.

Tariff note: TOU can still help if you sometimes charge in off-peak hours. Energy

5) Space-constrained or budget-constrained households

Typical pattern: limited available space, or you want the lowest initial investment.

Usually works well: solar-only now, “battery-ready” wiring/board allowances where possible.

Why: battery storage installation costs (plus switchboard work and electrical wiring) can lift the total cost fast.

Next move: use monitoring to see how much you export, then decide if a battery is a good idea later.

6) Remote locations / reliability issues

Typical pattern: you want less dependence on the power grid and fewer disruptions.

Usually works well: solar + batteries sized for real energy needs, with a proper design discussion (including battery chemistry and usable capacity). The point is energy independence and reliability, not just a prettier bill.

Two universal rules

- Hardware + compliance: choose inverters/panels/batteries that are eligible for Australian installation and rebates; the Clean Energy Council maintains approved product information and consumer guidance.

- Incentives in Australia: most home owners see STCs applied as an upfront discount in the quote.

Pick the profile above that matches your household, then write a one-line goal (“lower bills”, “backup essentials”, “EV-ready”, etc.).

Frequently Asked Questions

1) How big should my solar panel system be?

Big enough to cover a meaningful chunk of your daytime use without relying on exports to “pay it back.” Start with your bills and when you use power.

2) Do I need solar batteries to save money?

Not always. If you already use lots of power during the day, solar alone can cut electricity bills. Batteries help most when they reduce expensive evening imports or you want backup.

3) Will my solar power system work in a power outage?

Not automatically. Many grid-tied systems shut down in an outage unless your setup is designed and wired for backup circuits.

4) What are time-of-use electricity rates and off-peak hours?

TOU means electricity prices change by time (peak/shoulder/off-peak). Shifting usage (or battery discharge) away from peak can reduce energy costs.

5) What is a network tariff, and can I change it?

A network tariff is the pricing classification your distributor assigns based on connection type, metering, and usage pattern. Your retailer plan and your network tariff aren’t the same thing, and changing either may have conditions.

6) Is “net metering” a thing in Australia?

People say it, but Australia mostly uses feed-in tariffs (credits for exported solar) rather than the US-style “net metering” idea.

7) What battery chemistry should I look for?

Most home batteries are lithium-ion batteries, with many now using lithium iron phosphate. Ask about usable capacity, warranty terms, and cycle expectations—not just chemistry marketing.

8) Are lead-acid batteries still used?

Sometimes, especially in remote locations or legacy off-grid setups. For typical suburban residential use, lithium-based batteries are usually the default choice today.

9) What incentives exist in Australia for solar and batteries?

Solar commonly uses STCs under the Small-scale Renewable Energy Scheme (often shown as an upfront discount). Batteries may have additional support depending on program availability; the Clean Energy Regulator’s Cheaper Home Batteries Program page is the place to check current eligibility.

Further Reading

Member discussion