Condensation and mould aren’t “cosmetic issues”. On a job site, they’re a signal that excess moisture is sitting where it shouldn’t, long enough for a type of fungus to set up camp.

If it’s ignored, you don’t just get a mould problem — you get call backs, water damage, complaints about indoor air quality, and in the worst cases, arguments about health risks and structural damage.

The annoying part is that mould can look like it “came from nowhere”. The reality is simple: warm air holds much moisture. When that moist air hits cold surfaces, the air cools, moisture drops out as water droplets, and you’ve created a damp environment that supports indoor mould growth.

Add inadequate ventilation, and the risk of mould growth climbs fast

Walk the building early morning. Look for cold spots, fogging on glass, damp smells, and any fresh staining around penetrations and rough openings.

Why this happens on builds (and why “it’ll dry out later” is BS)

Condensation is physics

Condensation happens when a surface temperature drops below the dew point of the surrounding air. You don’t need a roof leak for that. You just need:

- humidity levels high enough, and

- surfaces cold enough, and

- enough time.

On builds, you get all three. In many climate zones, the job swings between hot/humid days and cool nights. The air temperature drops, the sheathing and framing cool down, and moisture in the air turns into water vapour on surfaces.

The jobsite creates moisture constantly

Even before you talk about rain, you’ve got moisture coming from normal work and everyday activities:

- Wet trades using warm water

- Fresh concrete, render, gyprock mud holding water and releasing water vapour

- Temporary heat sources and unvented combustion adding much moisture to the air

- Workers cooking, washing, and general daily activities in partially enclosed buildings

That’s why “it’s only a small area” can be misleading. Moisture migrates. It rides air currents as moisture-laden air, finds the first cold surface, and drops out.

Where condensation becomes a mould problem

Mould needs three things:

- Moisture (persistent high moisture levels)

- Food (often organic materials like paper-facing, wood dust, or dirt)

- Time

A lot of common building materials are surprisingly vulnerable. Some are porous materials that soak moisture and hold it:

- Paper-faced gyprock

- ceiling tiles

- Framing lumber with elevated moisture content

- Dusty OSB edges

- Cardboard packaging left in damp places

Once mould grows, it can release mould spores into the indoor environment. That’s when you get the occupant side of the problem: complaints about effects of mould, worries about toxic effects, and legitimate concerns around human health for people with respiratory conditions.

Why it’s more than “a little mould”

Not everyone reacts the same, but mould exposure can be associated with allergic reactions and respiratory problems.

People describe symptoms like nasal congestion, a runny nose, or worse in those prone to asthma attacks or other health conditions. Some occupants have compromised immune systems, and the fear of risk of health problems becomes a real escalation point.

As a builder, you just need to treat moisture like a defect generator and manage it like one.

Identify any rooms that were recently closed in after wet work (gyprock, tile, paint). If doors are shut and air isn’t moving, assume indoor humidity is high.

Where it shows up first (and how to diagnose it)

The usual hotspots

Condensation and mould don’t spread evenly. They show up where air flow is poor, surfaces are colder, or moisture is introduced repeatedly. On residential builds, watch:

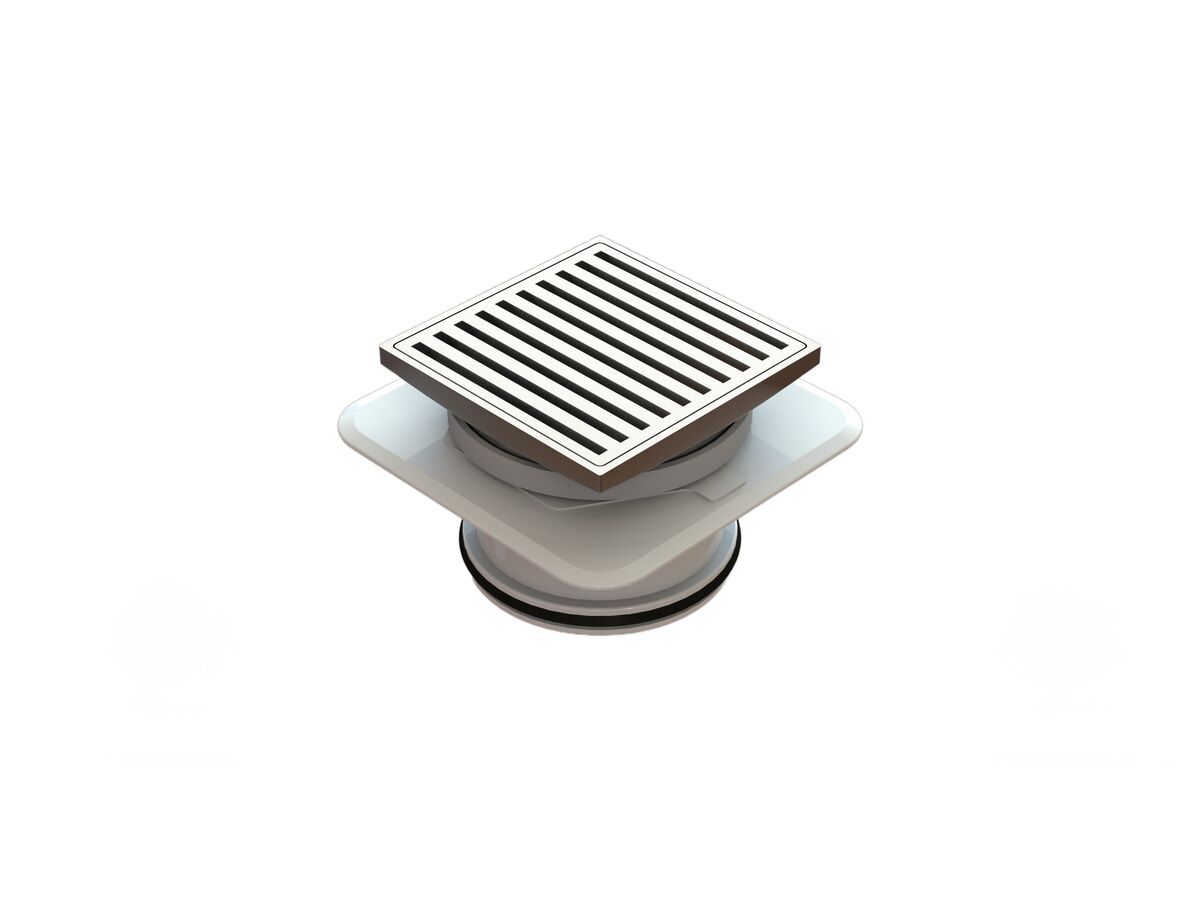

- Bathrooms, laundries, kitchens (high moisture)

- HVAC, wardrobes, plumbing vent pipes

- Behind insulation in exterior cavities

- Around window frames and window frames/rough openings

- On the interior side of external walls in colder seasons

- Roof spaces and roof space transitions

- Any “closed box” area in the house

The “window frame” tell

One of the fastest indicators is condensation on glass and around window frames. When people complain, it often starts with “water on the windows.” It’s a sign that interior relative humidity is too high, surfaces are cool, or both. It’s especially common when:

- HVAC isn’t commissioned yet

- The house is sealed tight

- Trades are running heaters

- Nobody is using exhaust fans / extractor fans

If the job is at lock-up and you can see water droplets collecting at the sill, you’re already in “fix this now” territory.

Visual inspection: what you’re actually looking for

A good visual inspection isn’t just “do I see mould”. It’s:

- Dark staining or fuzzy growth (obvious mouldy area)

- Repeated dampness at corners (often damp spots)

- Bubbling paint, swollen MDF, lifting flooring

- Rusting fasteners unusually early

- Musty smell (often present before visible mould)

If you find damp walls or persistent condensation on hard surfaces, treat it like a moisture pathway problem, not a cleaning problem.

The two measurements that count

You can diagnose most situations with basic measurements:

- Indoor relative humidity and air temperature

- Material moisture content (wood, subfloor, cladding edges)

High indoor RH plus cold surfaces equals risk. High moisture content in framing or sheathing means you need drying and air movement before you close it up.

Common root causes

When you trace the source, it’s usually one (or a combo) of these:

- Bulk water entry: water leaks at roofs, flashing, rough openings

- Plumbing: pinholes, bad caps, slow drips, supply line failures (water problem)

- HVAC: sweating ducts, poorly insulated lines, poorly sealed ducts wrong commissioning

- Air leakage: warm moist interior air moving into cold cavities

- Trapped moisture: too-tight assemblies without proper drying strategy

- Occupant conditions later: high indoor humidity from cooking, showers, drying clothes, etc.

You’ll often hear “just open windows.” Sometimes that helps, because it brings in outdoor air and reduces moisture concentration. Sometimes it doesn’t, because the outdoor air is humid too. The point is: ventilation is a strategy, not a slogan.

Inspect around windows and exterior corners first thing in the morning. If you see consistent condensation on window frames, log it and check RH on site.

Ah AC ductwork - have you ever seen a residential AC contractor that really cares about installation and compliance details? (Personally, I'm yet to find one)

Prevention during construction (and what to do when it’s already there)

Moisture control on site: the mindset

The best way to avoid mould is to stop giving it what it wants: sustained moisture. Think in layers:

- Keep bulk water out (roofing, flashing, drainage)

- Don’t trap wet materials inside

- Manage humidity with air movement and exhaust

- Use assembly choices that tolerate the climate and drying direction

This is where building design matters. Tight, efficient homes can be great — but they punish sloppy moisture management.

Read all about roofing and flashing here, in our C9 Checklist and explainer article.

Keep bulk water from becoming a water damage story

A water problem becomes water damage when it’s ignored long enough to soak framing or finishes. Key steps:

- Protect openings early. Don’t leave rough openings exposed “just overnight” before storms.

- Detail flashing and drainage properly at windows/doors.

- Don’t store gyprock, ceiling tiles, or flooring on slabs without a dry plan.

- If you’ve got repeated wetting events, assume elevated moisture content and verify before closing cavities.

If you’re building slab-on-grade, don’t gloss over capillary moisture. A proper vapour barrier under slabs is standard practice for a reason. (Some people will use “damp-proof course” language from masonry contexts; on slabs you’re usually thinking vapour retarder/barrier and capillary breaks.)

Ventilation: it’s not optional at the “closed-in but wet” stage

Drying happens when you move moist air away from wet materials. That’s why proper ventilation plays an important role during:

- Gyprock finishing

- Tile and grout curing

- Paint curing

- Flooring acclimation

Use mechanical exhaust where you can:

- Run exhaust fans in wet areas as soon as power is available

- Use temporary ventilation setups if the building is sealed

- Don’t rely on “crack a window” unless conditions support it

Yes, open windows can help sometimes. But in hot/humid regions, bringing in outdoor air can increase indoor humidity. Use your meter, not vibes.

Use vapour control layers like an adult

Vapour control layers aren’t about “always put wall wrap on the outside.” They’re about controlling where water vapour goes and where it can dry. The wrong layer in the wrong climate can trap moisture in cavities and create condensation problems that don’t show up until after handover.

So the rule of thumb is:

- Know your climate zone

- Know the intended drying direction of the assembly

- Avoid double vapour barriers that sandwich moisture

If you don’t know, don’t guess. This is the point where you bring in an envelope consultant, or you stick to proven local wall and roof assemblies.

And if you hear construction managers, salespeople, or anyone else say, “But we build brick veneer — it lets the house breathe and dry out,” that’s ignorance on display.

Sure, the house “breathes”… which often just means your conditioned air is leaking out, so your air con runs longer and you spend more money while your cool (or warm) air “breathes” its way outside.

A better approach is simple: reduce air leakage first, then manage and control the air inside the home, instead of trying to solve the problem by pumping in more cooled or heated air.

That doesn’t mean you need a “passive” house, either — just a few sensible design choices that help you control air movement between your control layers

Material storage and sequencing

Mould loves cardboard, dust, and damp. Keep materials dry and off the floor:

- Protect building materials from rain and slab moisture

- Don’t stack insulation in a damp cavity “for later”

- Remove wet packaging and debris (food for mould)

- Don’t close walls until moisture content is in a safe range

A lot of mould issues begin with “small amounts” of water that happen repeatedly: a bit of rain through a window opening, then a humid week, then the cavity gets insulated and sealed. Now you’ve created a hidden incubator.

Portable dehumidifiers: useful, but not magic

Portable dehumidifiers can be effective in a small area when the building is closed and you need to pull moisture down quickly. But they’re not a substitute for fixing the source and moving air. Pair them with airflow and, ideally, exhaust/return pathways.

When it’s already there: remediation basics

Once you’ve got a mouldy area, cleaning isn’t step one. Step one is stopping the moisture source.

Basic approach:

- Identify and fix water leaks or condensation drivers

- Dry the area fast (air movement + humidity reduction)

- Remove and replace water-damaged porous items (gyprock, insulation) if they’re contaminated

- Clean hard surfaces if mould is superficial and the material is salvageable

- Document everything: photos, readings, dates, what was removed/replaced

About chlorine bleach: it’s often brought up as a quick fix. On non-porous surfaces it can help disinfect, but it’s not a cure-all, and it doesn’t solve underlying moisture. Also, don’t encourage unsafe chemical use. Keep cleaning guidance conservative and aligned with product labels and safety requirements.

If the mould is extensive (“much mould” across multiple rooms), you’re beyond DIY site cleanup. That’s when you engage a qualified remediation contractor and follow containment and disposal practices.

If you’re about to install insulation or close walls, stop and measure moisture content. If it’s wet, you’re about to bury the problem.

Condensation and mould aren’t mysterious. They’re predictable outcomes of high humidity, cold surfaces, and trapped moisture.

The job is to manage excessive moisture the same way you manage fall hazards: with planning, controls, and verification.

The biggest mistake is treating mould like a cleaning problem. It’s a moisture and airflow problem. Fix the cause, dry the assembly, then fix what’s damaged.

Do that well, and you protect your house, your wallet, and the future occupants’ indoor air quality.

Want re learn/read more about condensation and Australian housing performance?

Read more about the quality of Australian housing construction, and how it contributes to condensation and mould issues.

Note: to date, none of the recommendations in this report have been implemented into construction standards. I’m assuming the building lobby and industry associations would prefer to keep things as they are — or, at best, fall back on the usual line: “It’ll only make houses cost more for consumers.” Anything, apparently, except building better homes for you and me to actually live in.

Their priorities are pretty clear — and improving construction quality isn’t high on the list.

FAQs

1) What’s the difference between condensation problems and a water leak?

A leak is bulk water entry (roof, plumbing, flashing). Condensation problems happen when moisture-laden air hits cold surfaces and turns into water droplets. Both can cause water damage, but the fix is different.

2) Why do windows sweat so much on new builds?

New builds often have high indoor relative humidity from wet trades and limited HVAC operation. Window frames and glass can be colder than surrounding surfaces, so moisture condenses there first.

3) Can mould affect people’s health?

It can. Some people report allergic reactions, nasal congestion, runny nose, or broader respiratory problems. People with respiratory conditions, weak immune systems, or a history of asthma attacks may be more sensitive.

4) Is all mould “toxic black mould”?

No. There are types of moulds, and not every type of fungus is the same. The practical takeaway is still the same: remove moisture, dry the area, remediate properly.

Keywords: types of moulds, type of fungus

5) What’s the fastest way to spot a mould issue during construction?

Start with visual inspection plus RH/temperature checks. Look for musty smells, staining, and damp corners. If you find a mouldy area, don’t just wipe it — find the moisture source.

6) Do exhaust fans really make a difference?

Yes. Exhaust fans and extractor fans remove moist air at the source (bathrooms, laundries). They’re one of the simplest controls for reducing indoor humidity and limiting mould risk.

7) Are portable dehumidifiers worth using on a job site?

They can help in a small area, especially after wet trades or minor water events, but they’re not a substitute for fixing leaks and ensuring proper ventilation.

8) Should I just open windows to ventilate?

Sometimes. Open windows can reduce humidity when the outdoor air is drier. But if outdoor air is humid, it can make things worse. Measure and decide.

9) Can bleach solve mould?

Chlorine bleach may help on some hard surfaces, but it won’t fix the cause (moisture). Don’t treat it as a primary solution, and follow label safety directions.

10) What’s the risk if I ignore a little mould during the build?

It can spread, damage porous materials, and lead to disputes about health effects and indoor air quality after handover. It’s also harder to remediate once finishes are installed.

Further Reading

Member discussion