Introduction: Housing Isn’t Just a Product—It’s Policy

Let’s get one thing straight from the beginning: housing isn’t just bricks, timber, tiles, and concrete. It’s not just a roof over your head or the dream of a first home. It’s policy. And not the kind of policy that floats above us in the clouds of Canberra, never touching down in real life.

We’re talking about policy that decides who gets to build, what they can build, where they can build it, and—importantly—who can afford to live in it.

But here’s the thing: housing policy in Australia has been shuffled around like a hot potato. Different departments, different ministers, different states, different rules—everybody wants a say, but nobody’s really in charge. That means we get patchy results, long delays, and rising costs. If you’re trying to build a home right now, chances are you’ve run headfirst into this mess.

This isn’t just frustrating—it’s costly. Not just for builders, but for everyday Australians who want to build, buy, rent, or simply find somewhere decent to live. According to the AHURI report we’re looking at in this article, Australia’s government approach to housing has been more “Frankenstein’s monster” than masterplan—stitched together, lurching along, and lacking any real coordination.

The problem? It’s not just who’s holding the hammer. It’s who’s holding the pen.

Because if policy keeps changing hands, structures keep getting torn down and rebuilt, and no one stays in the job long enough to finish what they start… the machine breaks. And when the machine breaks, you don’t get homes. You get housing shortages, skyrocketing prices, underfunded programs, and planning gridlock.

We’re here to explain how we got into this position—and how we might just dig ourselves out.

What Exactly Is Housing Policy?

You’ve probably heard the term housing policy tossed around—usually by politicians or economists.

But what does it actually mean? And why should homeowners, renters, and builders care?

Here’s the simple version:

housing policy is the sum of all the decisions governments make that affect who can live where, in what kind of housing, under what conditions, and at what cost.

Sounds broad? That’s because it is. And that’s part of the problem.

The AHURI report lays out a helpful way to think about this. It divides housing policy into two zones:

The “Core” of Housing Policy

This is the stuff you might expect—directly about housing:

- Social housing (public housing, community housing)

- Crisis accommodation for people experiencing homelessness

- Rental support like Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA)

- Residential tenancy laws

- Housing for people with disability (e.g. SDA under the NDIS)

These areas are clearly housing-focused. They're where most of the media attention and government funding announcements tend to land.

The “Periphery” of Housing Policy

Here’s where it gets trickier. Lots of decisions that don’t look like housing policy on the surface actually shape the whole market. For example:

- Interest rates and monetary policy (which determine how expensive your mortgage will be)

- Land use planning and zoning laws (which decide how much land is available to build on)

- Tax settings like negative gearing, capital gains concessions, and land tax

- Immigration policy (which increases demand)

- Retirement and superannuation policy (which encourages investment in property)

- Infrastructure investment (because you can’t live in a house that isn’t connected to anything)

These “peripheral” policies affect supply, demand, affordability, and location—but they’re often made by departments that don’t even talk to the housing department.

So, What’s the Problem?

The core and periphery often get pulled in different directions. One part of government might be trying to “improve affordability” while another ramps up tax breaks that push prices higher. Or a housing department might be investing in social housing while planning laws make it nearly impossible to get a development approved on time.

This creates a fractured, contradictory system where no one’s steering the ship. The AHURI report argues that housing policy can’t work if it’s split between dozens of departments, levels of government, and conflicting agendas.

And that’s not just words on paper. It shows up in the real world:

Long wait lists for housing, unaffordable rents, uncoordinated infrastructure, and developers chasing profit without much oversight on what actually gets built.

A Long History of Restructuring (and Confusion)

If there’s one thing Australia does consistently with housing policy, it’s reshuffling the deck chairs.

The AHURI report highlights a decades-long pattern where housing policy keeps getting moved around—from one department to another, from one minister to the next. Sometimes it’s under social services, other times treasury, or infrastructure, or even the environment.

The result? No long-term focus, no institutional memory, and a lot of confusion.

It’s what the report calls “perpetual machinery-of-government change.” Every time a new government takes over—or even when a minister wants to make their mark—housing policy gets a makeover. These aren’t always big public reforms. Sometimes it’s just changing who reports to whom, or which agency is responsible. But each change disrupts the system.

The Human Cost of Restructuring

Imagine trying to build a house while changing your builder, engineer, and site supervisor every six months.

That’s what housing policy looks like from inside the public service. According to interviews in the report, these changes:

- Undermine staff morale

- Waste resources on re-branding and reorganisation

- Interrupt service delivery to people in need

- Dilute specialist knowledge and expertise

In many cases, people who had decades of housing-specific experience were sidelined or pushed out in favour of generalist managers—people who might know how to run a department, but not how to manage a complex housing system.

Compare That to Other Portfolios…

Health, Defence, and Education rarely suffer from this kind of instability.

Why? Because governments see them as essential services.

They’re usually given consistent oversight, dedicated departments, and long-term planning.

Housing, by contrast, is treated like a political football—tossed around when it suits short-term agendas. This has real-world consequences.

It’s why we don’t have a consistent national housing strategy, why targets change with every budget, and why delivery of services is often patchy or reactive.

“Residualisation”: The Final Stage of Policy Neglect

Another term the report uses is residualisation. That’s a fancy way of saying public and social housing have been pushed so far to the margins that they’re now seen as “welfare housing”—only for people in extreme crisis.

The result?

A shrinking social housing system, rising waiting lists, and more pressure on the private market to absorb demand it was never built to handle.

4. Why Coordination Matters (And Why We Lack It)

Let’s say you’re building a home. One team lays the slab, another frames the walls, someone else installs plumbing, and a separate crew handles the roof. Now imagine none of them talk to each other. No plans are shared. No one’s sure who’s responsible for what. Sounds like a disaster waiting to happen, right?

That’s exactly what housing policy coordination looks like in Australia.

The Federal–State Split: A Recipe for Buck-Passing

In Australia, housing policy is divided between the federal government and the states. The Commonwealth handles things like:

- Commonwealth Rent Assistance

- Tax policy (negative gearing, CGT)

- National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC)

- Income support programs linked to housing affordability

Meanwhile, the states and territories are responsible for:

- Social and public housing stock

- Planning and zoning rules

- Approvals and land use

- Tenancy laws

- Local housing strategies

Each level of government has a role to play. But too often, the lines of responsibility are blurry—and when things go wrong, each side points the finger at the other.

A Real-World Example: The Missing Middle

You might’ve heard the term “missing middle housing”—think duplexes, townhouses, and low-rise apartments that fall between freestanding homes and high-rise towers. These are essential for affordable, medium-density living.

The problem? Local councils often block them due to zoning rules. State governments push for higher-density development, but they’re held up by council politics. And the federal government—while claiming to support affordability—has no direct power over local planning. So nothing gets built.

The Impact of Poor Coordination

Here’s what happens when policy isn’t aligned:

- Projects stall due to inconsistent planning laws and lengthy approval timelines.

- Social housing pipelines dry up because funding doesn’t match delivery capacity.

- Private developers dominate because they’re often the only ones nimble enough to work across different layers of regulation.

- Infrastructure gets left behind, with new developments popping up before transport, schools, or healthcare are in place.

The report argues that better coordination isn’t just a nice idea—it’s essential. Without it, the entire housing system is fragmented, reactive, and slow.

And guess who pays the price? You do. In the form of higher costs, longer wait times, and fewer housing options.

The Impact of Poor Administration on Homeowners

You don’t need to be a policy expert to know something’s broken in the system—you just have to try building or buying a home. Red tape, long delays, unexpected costs, and poor-quality outcomes aren’t just bad luck. They’re symptoms of a system that’s being poorly managed at almost every level.

The AHURI report lays it bare:

When housing policy is badly administered, the effects trickle down fast—and they hit homeowners and renters square in the back pocket.

Delays in Development and Approvals

Poor coordination and constant government restructuring create bottlenecks in development approvals. Councils might take months (or years) to approve a new estate or infill project. States might update planning codes mid-way through a project. And federal infrastructure funding might not match the pace of new development.

All of this means fewer houses get built. And when supply doesn’t keep up with demand? Prices rise. It’s that simple.

Costs Blow Out (and So Do Your Stress Levels)

When approvals stall and regulations clash, developers pass the cost downstream. Builders price in delays. Homeowners pay for holding costs. Buyers pay more for homes that took too long to hit the market. And let’s not forget the hidden cost: quality.

In a system driven by quick turnarounds and inconsistent oversight, some builders cut corners. Dodgy work slips through the cracks, and homeowners are left dealing with defects that should’ve been picked up and fixed long before handover.

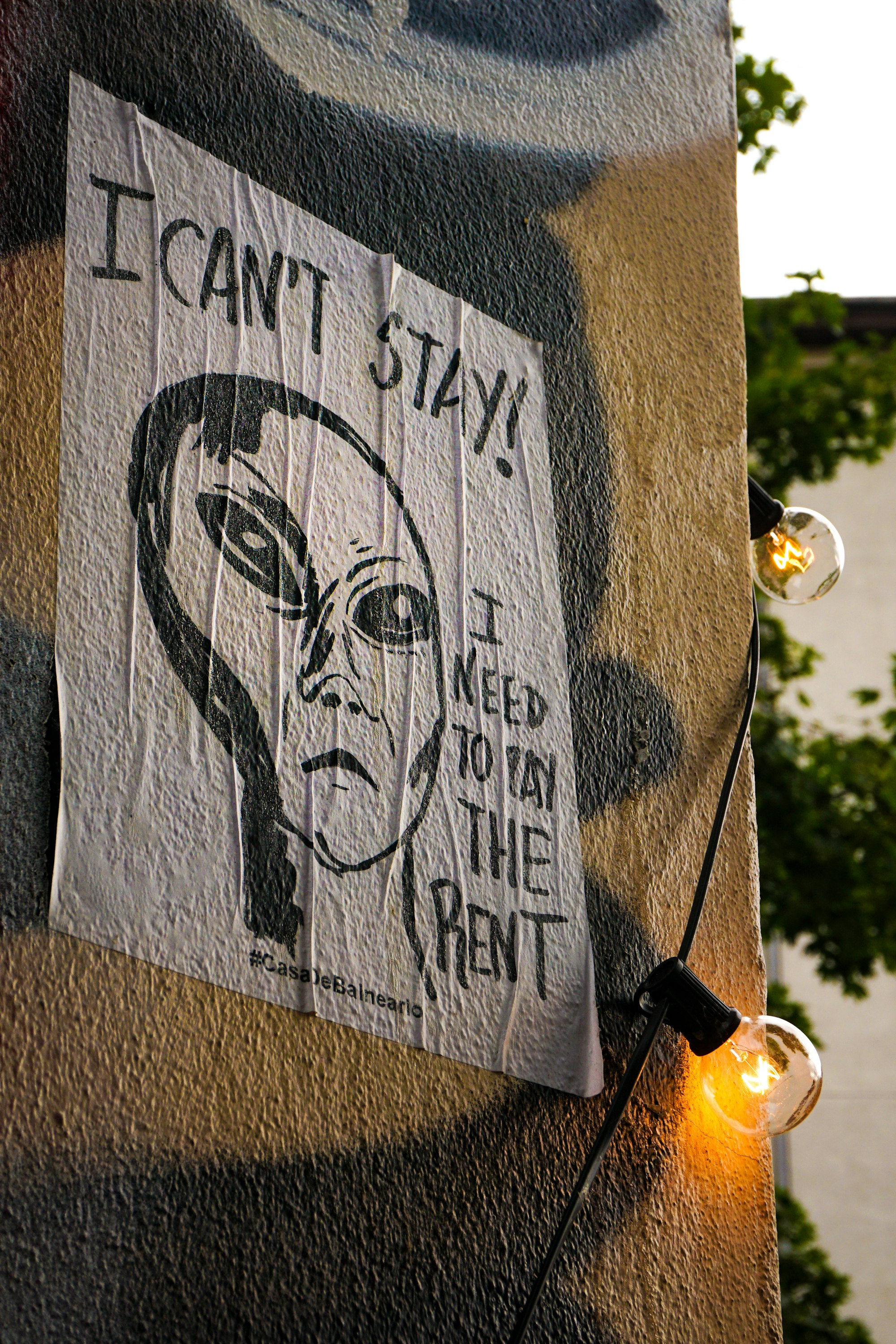

Housing as Investment, Not Shelter

The current system rewards speculation and penalises long-term ownership. Why? Because policy has been shaped around encouraging investment—through negative gearing, tax incentives, and capital gains discounts—rather than delivering stable, affordable housing for everyone.

This distortion benefits property investors over owner-occupiers, inflates prices, and shifts housing away from its purpose as shelter and into the world of financial products.

The people losing out?

First-home buyers, single-income households, young families, and renters trying to make the leap into ownership.

Market Capture and Lack of Oversight

The report also hints at a deeper issue: market capture. When government oversight is weak or inconsistent, large private developers can end up shaping policy themselves—whether through lobbying, donations, or just sheer scale. This risks locking in a system that works for profit margins, not people.

That’s not to say private industry doesn’t have a role to play—it does. But without strong public leadership, enforced standards, and strategic planning, the balance tips in favour of developers.

The result is often cookie-cutter housing in the wrong places, with little thought to long-term liveability.

👉️ What the Report Recommends: A Better Way Forward

So, how do we fix a system that’s been chopped, changed, and scattered across departments for decades?

According to the AHURI report, it’s not just about spending more money—it’s about changing how the system is run from the top down.

👉️ Here’s what the experts are proposing:

Create a Cabinet-Level Department of Housing

The report strongly recommends the establishment of a dedicated federal Department of Housing—one with its own Cabinet Minister, its own legislation, and its own clear mission. This would:

- Give housing policy consistent leadership

- Shield it from constant reshuffles

- Enable long-term planning that survives election cycles

This isn’t a crazy idea—other countries already do it, and even Australia has done it before. But the current practice of burying housing within other portfolios (like infrastructure or social services) weakens its impact and priority.

A National Housing Framework—With Legal Teeth

The report pushes for a national legislative framework for housing, similar to Canada’s. This would:

- Set long-term goals and strategies in law

- Define the roles of each level of government

- Protect housing outcomes from political back flips

It’s not about overreach—it’s about clarity and accountability. With a legal foundation, governments couldn’t just abandon housing goals without scrutiny.

Centralise Policy, Decentralise Delivery

Instead of every state and territory inventing their own approach, the report suggests centralising housing policy design at the federal level, while letting local governments and community providers handle delivery. This keeps things tailored to community needs, but aligned with national standards and goals.

Back the Not-for-Profit Sector

Rather than rely solely on profit-driven developers, the report recommends giving non-profit and community housing providers more resources, authority, and access to finance. These providers often deliver better-quality, longer-term housing outcomes—but they’re constantly under-resourced and treated as a backup, not a first option.

Less Faith in “The Market Will Fix It”

The report doesn’t say to scrap private developers.

—it says stop pretending they’ll deliver affordable, inclusive housing without guidance.

It calls for:

- Stronger regulation

- Better incentives for delivering affordable housing

- A shift away from using housing as a wealth-generation tool

Instead of hoping the private sector will fill gaps, governments should plan for and actively shape the outcomes they want.

Lessons from Overseas: What We Can Learn

Australia’s not the only country wrestling with housing affordability and policy chaos—but some have managed it far better. The AHURI report points to a few international standouts that show what’s possible when governments take housing seriously, treat it as a public good, and design policy for the long term.

🇨🇦 Canada – Rights-Based Policy With National Vision

In 2019, Canada passed the National Housing Strategy Act. This law doesn’t just set a goal—it enshrines the right to housing in legislation. They’ve also established:

- A Federal Housing Advocate, who monitors performance and gives independent advice

- A National Housing Council, which includes voices from across the sector

- A long-term national strategy backed by measurable outcomes

The key difference? These mechanisms are legislated, not just political promises.

🇫🇮 Finland – Central Agency, Long-Term Thinking

Finland’s housing policy is delivered through a single government body: ARA (The Housing Finance and Development Centre). ARA handles everything from:

- Financing new affordable homes

- Allocating subsidies

- Enforcing quality and access rules

- Advising government on housing needs

It’s centralised, consistent, and long-term. They’ve also effectively ended rough sleeping through their “Housing First” approach, which prioritises stable accommodation before tackling other social issues.

🇦🇹 Austria – Regulated Non-Profits at Scale

Austria’s model might be the most surprising: limited-profit housing associations deliver around 25% of the country’s housing stock. These associations:

- Must reinvest profits into housing

- Operate under strict cost-rent rules

- Are supported by low-interest loans and government land

The result is a thriving rental market, high housing quality, and far less volatility than markets like Australia’s. People rent for the long term—by choice, not just necessity.

🧩 What These Countries Get Right

- Policy stability: Housing isn’t constantly being restructured or deprioritised.

- Clear accountability: Independent bodies monitor progress and report to the public.

- Public-good mindset: Housing is seen as infrastructure, not just an investment.

- Strong community role: Not-for-profits and community groups aren’t an afterthought—they’re central to delivery.

🇦🇺 Why Australia Falls Short

Australia, in contrast, has:

- No national legislation on housing rights

- A fragmented policy landscape

- Weak central oversight

- Heavy reliance on the private market for outcomes it has no obligation to deliver

In other words, we’ve tried the “hands-off” approach—and it’s not working.

🤔 Why We Need to See Housing as a Human Right

If there’s one message the AHURI report belts you with, it’s this: we need to stop treating housing like a product and start treating it like a right.

That doesn’t mean every Australian gets a free house. It means recognising that secure, affordable, and decent housing is as fundamental as access to healthcare or education.

And just like those systems, housing needs:

- Long-term investment

- Clear public policy

- Accountability

- Oversight

Why the “Market First” Approach Falls Short

Right now, Australia leans heavily on the private market to deliver housing outcomes. But private developers aren’t public servants. Their goal is to turn a profit—and fair enough. That’s what business is.

The problem is when we expect business to deliver what government won’t: Affordable homes, long-term rentals, and housing in the right places for the right people.

That’s not what the market is built for. And it’s why we end up with:

- Investor-driven apartment blocks in areas with no infrastructure

- First home buyers pushed out by speculative demand

- Social housing waiting lists growing year after year

Dealing With Stigma and the “Welfare Housing” Narrative

We’ve also let social housing become stigmatised—as though it’s only for people who’ve “failed” at home ownership. This ignores the reality that:

- Wages haven’t kept up with housing costs

- Renting offers little long-term security

- Many working families now rely on housing support

A Rights-Based Framework Makes Governments Accountable

Declaring housing a human right isn’t just symbolic. When countries like Canada did it, they also created:

- Independent housing advocates to track progress and flag problems

- Legal obligations to report on housing targets and outcomes

- Mechanisms for public input, especially from people directly affected

This turns housing from a vague goal into a measurable commitment.

Conclusion: Stop the Chaos, Start the Reform

After decades of policy churn, missed targets, and rising housing stress, one thing is clear: we don’t have a housing shortage—we have a coordination problem.

The AHURI report doesn’t point fingers at any one party or minister. Instead, it highlights a deeper issue: The structure of how we manage housing in Australia is broken. Unless we fix that structure, no amount of spending, or incentives will turn things around.

We’ve Tried the Patchwork Approach. It Doesn’t Work.

Housing has been tacked onto infrastructure here, social services there, planning departments elsewhere. It's been everyone’s job and no one’s responsibility. The result? A system full of gaps—and homeowners, renters, and builders falling through them.

We don’t need more pilot programs. We don’t need another roundtable. We need reform with real backbone.

What Real Reform Looks Like

Based on the report, here’s what that reform should include:

- A dedicated federal housing department, properly resourced and protected from political whim

- A legislated national housing strategy, with clear roles and reporting

- Stable leadership, not just across election cycles, but across generations

- Support for the not-for-profit sector, so affordable housing isn’t left to market chance

- A shift in mindset—from housing as a commodity to housing as a public good

These ideas aren’t radical. They’re common sense. And they’re already working overseas.

Why It Matters for You

If you’re planning to build, trying to buy, or stuck renting, this might all sound like it’s above your pay grade. But it’s not. The structure of housing policy affects everything—what gets built, how much it costs, where you can live, and whether you’ll be stuck waiting while governments play musical chairs.

When housing policy is treated as an afterthought, people pay the price.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What does “machinery of government” mean in the context of housing?

It refers to how government departments and responsibilities are structured—who makes decisions, which agency does what, and how housing policies are designed, funded, and delivered. Constant changes to this machinery in Australia have led to confusion, inefficiency, and poor outcomes.

2. Why is housing policy split between federal and state governments?

Because Australia’s Constitution assigns different responsibilities to each level of government. The federal government controls things like tax, welfare, and finance, while the states manage planning, public housing, and land use. Without clear coordination, this split often causes overlap, delays, or gaps in delivery.

3. How does this affect the average home buyer or renter?

When responsibilities are unclear, decisions get delayed. Projects stall. Housing stock lags behind demand. Costs go up. Whether you’re building a new home or trying to rent, these policy failures show up in your budget, wait times, and options.

4. What’s the downside of constantly moving housing policy between departments?

It destroys continuity, erodes institutional knowledge, and makes long-term planning almost impossible. Each restructure means delays, re-branding, new leadership, and disruption to services. It’s like rebuilding the foundations every time a new minister walks in.

5. Is treating housing as a human right just symbolic?

No. Countries like Canada back it up with legislation, housing advocates, and accountability mechanisms. It shifts housing from being treated as a market-driven asset to something the government must plan for and protect, like healthcare or education.

6. Why hasn’t Australia followed international models like Finland or Austria?

Partly because of ideology—there’s been a strong reliance on market-led housing in Australia. There’s also a lack of long-term planning structures and resistance to giving more power to public or not-for-profit housing bodies. The report suggests we need a cultural and structural shift to catch up.

7. Can private developers fix the housing crisis?

Not on their own. Private developers build for profit, not public need. Without clear rules, incentives, and oversight, they’ll keep building what’s most profitable—not what’s most needed.

8. What is “residualisation” of social housing?

It means public and social housing has been pushed to the fringe—seen as only for people in crisis, rather than as a normal part of a healthy housing system. This mindset limits investment and increases stigma.

9. What role do not-for-profits play in housing?

A huge one—especially overseas. Countries like Austria and Finland support limited-profit housing associations that build affordable, high-quality housing at scale. In Australia, this sector is underfunded and often sidelined.

10. What’s one thing I can do as a homeowner or future buyer?

Stay informed. Push for policy that values housing as a public good. Support reforms that call for transparency, structure, and long-term planning—because the decisions made in Parliament shape what happens in your postcode.

Further Reading