Introduction: Why Timber Matters to Your New Home

When most people think about building a new home, they picture floor plans, paint colours, or maybe where the couch is going to go. Rarely do they think about where the timber for the frame is coming from—or whether there’ll be enough of it to go around. But maybe they should.

Timber is the backbone of most new Australian homes. From wall frames to roof trusses, from floorboards to fascia strengthening, timber is everywhere. So if the supply of timber is short, slow, or expensive, it has a direct impact on your build—whether it’s delays, higher costs, or the need to swap materials.

That’s exactly why the federal government commissioned the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) to take a proper look at where our timber volumes are heading. After the chaos of the COVID construction boom—and the timber shortages it triggered—it’s become clear that better planning is needed if we want to avoid future supply shocks.

The result? A new report called “Australian Wood Volumes Analysis”, which forecasts the amount of timber Australia is expected to produce between now and 2050.

It details how much wood we’re growing, which types are rising or falling, and how that aligns with the housing and construction industry’s future needs.

You don’t need to be a forester to care about this. If you're planning to build a house, renovate, or just want to know why your builder is suddenly quoting more for a timber deck—this directly affects you. The big question is whether Australia’s timber supply is keeping up with the future we’re building towards.

In this post we’ll walk through the main findings of the report, what it means for your future home, and why timber supply should matter just as much as finding the right kitchen tapware.

👉️ Timber in Australia: A Quick Overview

Before we get into forecasts and future supply, it’s worth understanding where timber in Australia actually comes from—and what types are used for different parts of a home.

Let’s start with the basics: Australia’s timber industry is divided into three broad categories:

1. Softwood Plantations

This is the workhorse of Australian housing. When you hear about framing timber—like pine used in your walls and roof trusses—it’s almost always softwood. These are plantation-grown trees, usually radiata pine or slash pine, grown specifically for construction and harvested on a rotating basis.

Most new detached homes in Australia use softwood for structural framing. It’s strong, light, easy to work with, and—until recently—was relatively affordable and abundant.

2. Hardwood Plantations

These aren’t used much in house construction. In fact, most hardwood plantations in Australia are grown for export, and the bulk of it goes into woodchips for paper production, not floorboards or beams.

That might sound surprising, but these trees are often grown on short rotations and aren’t ideal for structural use unless they’re part of a specialised processing stream.

The report notes that hardwood plantations, while growing in size, don’t currently fill the construction-grade timber gap.

3. Native Forests

This is where most of Australia’s high-quality hardwoods have traditionally come from. Think spotted gum floorboards, jarrah stairs, or blackbutt decking. These are strong, durable, and often prized for their appearance.

But here’s the catch: logging of native forests is on its way out. Western Australia and Victoria are ending native hardwood harvesting for environmental and sustainability reasons, and Queensland and NSW are under pressure to do the same. That means we’re entering a future with a shrinking supply of native hardwoods—and not many obvious substitutes.

👉️ The COVID Timber Spike: What Happened and What We Learned

If you built—or tried to build—a home during the COVID period, you probably remember the chaos. Prices went up. Frames were delayed. Builders scrambled to get materials. At one point, timber became so scarce that some builders were sourcing framing packs from as far away as Europe, or pausing jobs mid-construction waiting on deliveries.

So, what actually happened?

The Perfect Storm

When COVID hit, the government rolled out stimulus programs like HomeBuilder to keep the construction industry moving. It worked—but almost too well. New home approvals surged. Renovation activity spiked. Everyone wanted to build at the same time.

The problem was, the global supply chain was already wobbling. Sawmills in Australia and overseas were short-staffed or shut. International freight costs soared. And just as demand went through the roof, the availability of construction-grade timber fell off a cliff.

According to the report, imports usually make up about 25% of Australia’s structural softwood consumption. But during the pandemic, import volumes dropped by as much as 60% in some months. That shortfall wasn’t easily replaced—especially not from local plantations, which take decades to mature.

What Did We Learn?

First, that we’re more dependent on imports than most people realise. When global shipping gets messy or offshore supply dries up, Australian builders feel it fast.

Second, that our domestic processing capacity isn’t as nimble or scalable as it needs to be. We had standing timber in the ground, but we couldn’t just ramp up local sawmills overnight to meet the surge.

And finally, the COVID timber shortage showed how fragile and interconnected the system is. A shock in one part of the world can quickly flow through and disrupt building projects here.

The takeaway? Relying on “just-in-time” imports for a core construction material like timber carries real risk. The pandemic was a wake-up call.

👉️ Where Demand Is Heading (and Why It Won’t Slow Down)

If you thought the timber crunch during COVID was a one-off, think again. According to the ABARES report, the demand for timber—especially structural timber used in housing—isn’t slowing down anytime soon. In fact, it’s going up. Way up.

More People = More Homes = More Timber

Australia’s population is projected to grow significantly between now and 2050, and with it comes a rising demand for housing. More detached homes, more townhouses, and more medium-density development all require timber—particularly plantation softwood.

Detached houses, in particular, are timber-hungry. The report estimates that a two-storey detached home uses roughly 14 cubic metres of structural timber. That’s a whole lot of pine. Apartments, by comparison, use far less timber per unit—sometimes less than 2 cubic metres—because concrete, steel, and other materials dominate in mid-rise and high-rise construction.

Timber’s Role in the Housing Mix

Even with growing urban density and planning shifts towards townhouses and apartments, timber is still central to how we build.

Timber frames are fast to install, lightweight, easy to work with, and well-understood by tradies. That’s unlikely to change quickly.

Add to this the push for more sustainable, renewable materials, and timber’s future looks even more in demand. Unlike concrete or steel, timber is a renewable resource—and when sourced responsibly, it can reduce the embodied carbon of your home.

Emerging Trends: Mass Timber Construction

The report also touches on engineered and “mass timber” systems—think cross-laminated timber (CLT), laminated veneer lumber (LVL), and glulam beams (GLT). These materials allow timber to be used in mid-rise buildings and commercial construction where traditionally only concrete or steel would do.

While promising, their use in housing is still emerging and under-reported in official figures. But if these technologies mature, they could provide a new outlet for plantation logs and reduce reliance on less sustainable alternatives.

👉️ Softwood: The Real Backbone of Aussie Housing

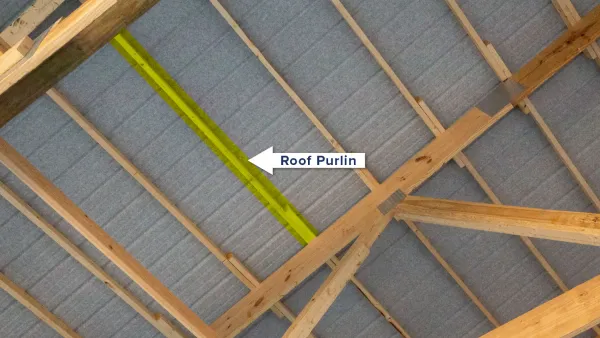

When it comes to what holds up most Australian homes, softwood is doing the heavy lifting. It’s what frames your walls, supports your roof, and forms the skeleton of almost every new detached house built in the country.

And while there’s been a lot of concern about timber shortages, here’s the good news: we’re actually growing more softwood than ever before.

Softwood = Structural Timber

Softwood plantations—primarily radiata pine and southern pine—make up the bulk of Australia’s construction timber supply. These trees are grown on 25–30 year cycles, are relatively fast-growing, and are ideal for sawing into structural framing timber.

Almost all of it comes from plantation forests, which are intentionally managed for high-volume, consistent supply.

And according to the ABARES analysis, softwood availability is set to increase by about 70% by 2050.

That’s the strongest forecast out of all timber categories in the report.

So, if you’re building a standard house, the structural timber that holds it all together should be increasingly available—at least in theory.

But Here’s the Thing...

More logs in the ground doesn’t automatically mean more timber on-site.

The real bottleneck lies in what happens after the tree is cut down. Australia’s domestic saw-milling and processing capacity has been struggling to keep pace with demand. Equipment is ageing, investment in capacity has lagged, and there’s limited ability to quickly scale up production during boom cycles.

Worse, if prices are better overseas, growers might export logs rather than sell them to local mills. That’s already been happening, with some plantation logs shipped out for processing elsewhere—only to be re-imported later as value-added products (at a higher cost).

So while the future of softwood supply looks strong on paper, it’s the processing pipeline that needs attention if we want to see the benefits at the building site.

👉️ Native Hardwood: High-Value, Low Supply

If softwood is the workhorse of the construction world, native hardwood is the premium upgrade. It’s what people turn to for things like beautiful polished floorboards, solid timber stairs, exterior cladding, or decking that can take a beating from the Aussie sun. But there’s a big shift underway—and it’s not good news if you love the look (and strength) of native hardwood.

Logging Is Being Phased Out

In recent years, several states have moved to shut down native forest harvesting. Western Australia and Victoria have both announced an end to commercial native logging on public land, and other states like Queensland and New South Wales are under pressure to follow. Environmental concerns, biodiversity, and carbon storage are driving the change.

That means less native hardwood available in future—and we’re already seeing the effects.

As the report points out, Australia’s supply of native hardwood logs for saw-milling has been declining steadily and will continue to fall.

No Easy Substitutes

Unlike softwood, you can’t just plant a native hardwood and harvest it in 20 years. These trees grow slowly—think decades, not years. And while plantations do exist, they mostly produce pulp logs for export (e.g. for paper), not high-grade saw-logs suitable for building materials.

There’s also the issue of performance. Native hardwoods are incredibly strong and durable, especially when exposed to the elements. For example, spotted gum or blackbutt decking will last much longer than pine alternatives, even when treated.

Unfortunately, there are no direct one-for-one replacements for some of these native timbers, especially if you care about structural integrity and appearance.

Imported hardwoods may be an option, but they come with their own challenges—price, quality control (moisture content, cupping, twisting, warping = waste = higher costs), and environmental impact.

Private Native Forestry: A Maybe

The report mentions that private native forestry—where landowners harvest timber from their own bush blocks—could help fill part of the supply gap. But it’s unlikely to cover the shortfall entirely, especially for the high-volume, high-grade timber that builders rely on.

👉️ Engineered Wood and Panels: Filling the Gaps (Maybe)

With native hardwood supply shrinking and softwood processing stretched, where do we turn next? Enter engineered wood products—an increasingly important piece of the puzzle.

What Are We Talking About?

Engineered wood includes a range of products made by gluing, compressing, or layering timber together. This includes:

- MDF (Medium Density Fibreboard) – used in cabinetry and fit-outs

- Particleboard – found in subfloors and benchtops

- Plywood – often used in bracing, wall linings, or formwork

- LVL (Laminated Veneer Lumber) – for strong structural members

- CLT (Cross-Laminated Timber) and GLT (Glulam) – part of the “mass timber” revolution

These products make use of smaller logs or off-cuts and can be engineered for strength, size, or fire performance—making them ideal for various structural and non-structural applications.

The Benefits

Engineered wood is efficient. It allows us to get more usable material from each harvested tree, and it can be tailored to meet specific building needs. Many engineered products are made from fast-growing plantation species, which also helps reduce pressure on native forests.

They’re also easier to transport and install, often coming pre-fabricated or dimensionally stable, which speeds up construction and cuts down on waste.

But There’s a Catch (Again)

While demand for engineered wood is rising, the report highlights a key issue: under reporting and under investment. There isn’t great national data on how much is being used, where it’s going, or how it’s performing in residential construction at scale.

And although there’s real potential for engineered timber to soak up excess pulp logs or reduce reliance on imports, this will only happen if the domestic manufacturing industry grows—and that means investment, infrastructure, and demand certainty.

Right now, a lot of engineered products used in Australia are still imported. Until that shifts, we remain exposed to many of the same risks we saw during the COVID supply crunch.

👉️ Domestic vs Imports: Can We Build Our Way Out?

Here’s the million-dollar question—can Australia produce enough timber locally to meet future demand, or will we always need to rely on imports to fill the gap?

The answer? It’s complicated.

The Role of Imports

Imports have long been a part of Australia’s timber supply chain. Around a quarter of our structural softwood is imported in normal years, often from countries like New Zealand, Germany, and the United States. When demand spikes (as it did during COVID), those import figures usually rise—assuming the global supply chain isn’t also under pressure.

Imports are particularly important when it comes to high-value or specialist timber products that we don’t make at scale here. That includes certain types of engineered wood, hardwoods, and decorative finishes.

But relying on imports comes with risks. Shipping costs fluctuate. Delays happen.

Global competition can drive up prices. And there’s always the chance that exporting countries prioritise their own needs first—as we saw when supply chains were squeezed in 2020–21.

Domestic Processing Is the Weak Link

One of the key takeaways from the report is that Australia’s ability to process the timber it grows is limited. We have standing trees—particularly softwood plantations—but not enough modern sawmills or engineered wood factories to turn logs into the building products our housing sector needs.

In some cases, plantation logs are being exported raw because local processors can’t match the price or volume demands. That’s not just a missed opportunity—it’s a sign that the system isn’t working as well as it should.

To reduce our dependency on imports, we don’t just need to plant more trees. We need to upgrade our processing capability, improve technology, and create more certainty in the domestic supply chain so that businesses have confidence to invest.

Until then, builders (and homeowners) will continue to face a mix of locally produced and overseas-sourced timber—with all the uncertainty that goes with it.

👉️ What About Climate Risks and Fire?

It’s hard to talk about Australia’s timber future without addressing the elephant in the room: climate risk. Drought, bushfires, floods—they all affect how, where, and whether timber can be grown at all.

Bushfires: A Double-Edged Sword

The 2019–2020 bushfire season devastated large areas of native forest and plantation land. For timber producers, this creates a tricky situation. In the short term, salvage logging can increase the volume of available timber—burnt trees can sometimes still be milled if processed quickly. But over the long term, it creates a hole in supply. Once burnt, it takes decades for a plantation to recover—if it recovers at all.

The report notes that climate-driven events like bushfires could create sudden spikes in supply followed by long lulls in availability, making long-term planning and pricing more difficult for everyone—especially builders and homeowners.

Drought and Heat Stress

It’s not just fire. Drought, extreme heat, and changing rainfall patterns affect tree growth. Trees under stress grow slower, yield lower volumes, and may be more prone to pests or disease.

Some regions—especially inland areas—could become less suitable for plantation forestry in the future. Meanwhile, others like Tasmania may actually benefit from a warmer climate, as longer growing seasons could improve yields there. But that kind of regional shift takes time and planning.

Insurance, Cost, and Uncertainty

There are also indirect effects. Timber producers are now paying more for insurance. Fire protection measures and site management costs are going up. These costs eventually trickle down the supply chain and end up in your builder’s quote.

Put simply, climate change isn’t just an environmental issue—it’s a timber supply and affordability issue too.

👉️ Land, Logs, and Long-Term Thinking: What Needs to Change?

If there’s one thing the ABARES report makes crystal clear, it’s this: timber supply doesn’t change overnight. Trees take decades to grow. So if we want to have the right timber available in 2040 or 2050, we have to start planning now.

Plantations Take Time

It takes about 25–30 years to grow a softwood tree ready for milling. Hardwood? Even longer. That means the timber we’ll use to build homes in the 2040s is already in the ground—or isn’t.

That’s why long-term planning is so important. But right now, plantation expansion has stalled. High land prices, limited government incentives, and regulatory complexity are all making it hard to establish new forests. In fact, the total area of plantations in Australia has actually declined in the past decade.

If that trend continues, we’ll face an uncomfortable future: more people needing homes, but fewer domestic trees to meet the demand.

Better Data, Better Planning

The report also points out that we lack reliable, up-to-date data on timber usage—especially when it comes to engineered products. Without this information, it’s hard for policymakers and investors to make smart decisions about where to plant, what to grow, and how to process it.

That’s a major barrier to improving supply chains and building a future-proofed timber industry. If we can’t measure it, we can’t manage it.

Processing and Manufacturing Innovation

On top of growing more timber, we also need to use what we have more efficiently. That means investing in modern processing equipment, expanding engineered wood capacity, and finding better ways to turn pulp logs or lower-grade timber into useful construction materials.

These aren’t just “nice to have” ideas—they’re essential if we want to reduce import reliance, boost local jobs, and keep construction costs under control.

👉️ What This Means for Homeowners and Builders

So, what does all this mean if you’re building a home—or thinking about it—in the next few years?

It means timber isn’t just “a product”—it’s a variable. One that can affect your budget, timeline, material choices, and even resale value.

Understanding how timber supply works helps you make smarter decisions before you sign a contract or approve that variation.

Pricing Volatility Isn’t Over

The sharp price hikes during COVID might’ve eased a little, but don’t expect a return to “cheap and easy” any time soon. Demand is still high, processing capacity is tight, and climate risks remain. As the report makes clear, Australia’s timber supply chain is still vulnerable.

Even if we avoid another crisis, price fluctuations are likely to continue—especially for hardwoods and imported products. That means quotes might expire faster, and builders may include more provisional sums or contingencies for timber materials.

Build Timing Matters

If you’re planning to build during a peak season—like when new grants are announced or interest rates drop—be prepared for lead time blowouts. Timber shortages are often at their worst when everyone’s trying to build at once.

Ask your builder how they manage procurement and if they’ve locked in materials. Don't assume everything is sitting in a warehouse ready to go.

Timber Quality Impacts Longevity

Where your timber comes from also affects durability, maintenance, and even warranty performance. For example, treated pine from a reputable domestic supplier may be better suited to local conditions than a generic imported equivalent.

Likewise, if you’re using hardwoods for stairs, decking, or flooring, make sure they’re properly graded and sustainably sourced—cheaper isn’t always better when you factor in lifespan and repair costs.

Don’t Be Afraid to Ask Questions

Builders aren’t always upfront about where timber is sourced or what happens if there’s a delay. But it’s your home, your money, and your risk—so ask.

- Where is the timber coming from?

- What happens if that supplier can’t deliver?

- Are any of the timber prices provisional?

- What alternatives are available if supply becomes an issue?

You don’t need to be a timber expert—you just need to be informed enough to spot a red flag.

👉️ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is Australia running out of timber for construction?

Not exactly—but supply is tight. Softwood plantations are increasing, but native hardwoods are declining, and processing capacity is under strain. The issue isn’t just trees—it’s turning them into usable building products.

2. Why did timber prices spike so much during COVID?

Demand surged due to stimulus programs like HomeBuilder, while global supply chains collapsed. Sawmills couldn’t keep up, and imports slowed—leading to shortages and soaring prices.

3. Will timber get cheaper in the next few years?

Not likely. Demand continues to grow, and while softwood supply is improving, processing and logistics costs are still high. Prices may stabilise somewhat, but “cheap” timber probably isn’t coming back.

4. Is engineered wood a reliable alternative to solid timber?

Yes—for many uses. Products like LVL, CLT, and plywood are strong, stable, and efficient. But they’re not suitable for every application, and Australia still relies heavily on imported versions.

5. Can I still get native hardwood for my floors or deck?

Yes, but expect to pay more and wait longer. Supplies are dwindling due to state logging bans, and there are limited substitutes for high-grade native hardwood in certain applications.

6. Why doesn’t Australia just import more timber?

We do—but imports come with higher costs, delays, and global competition. During supply crunches, we’re not the only country trying to buy up timber, which means prices go up and shipments slow down.

7. How much timber is used in a typical house?

A two-storey detached home can use around 14 cubic metres of structural timber. Apartments and townhouses generally use less, depending on design and materials.

8. Does climate change really affect timber supply?

Yes. Bushfires, droughts, and changing rainfall patterns impact forest health and long-term yields. Climate risk also increases costs for growers and adds volatility to supply.

9. Will mass timber like CLT replace concrete and steel in homes?

Not completely, but it’s gaining traction—especially in commercial and mid-rise buildings. It may become more common in residential builds, but right now, uptake is limited and still evolving.

10. What should I ask my builder about timber supply?

Ask where their timber comes from, if any quotes include provisional allowances, and what their plan is if materials are delayed or prices increase. It’s better to know upfront than be caught off guard.

🔍 Further Reading

Member discussion