Introduction: Why Housing Affordability in Australia is a Burning Issue

Let’s be honest: buying a home in Australia today feels like demolishing a ghost pepper curry and then discovering you're stuck in peak-hour traffic with no off ramp in sight. 🌶️🌶️🌶️💩💩💥

For most Aussies, the dream of home ownership is drifting further out of reach, thanks to skyrocketing property prices, soaring rents, and stagnant wage growth. In fact, recent data shows it now takes over 10 years to save for a standard deposit in capital cities—compared to just over 8 years back in 2003.

Add to that an alarming 49% of household income now eaten up by mortgage repayments, and it’s clear we’ve got a full-blown crisis on our hands.

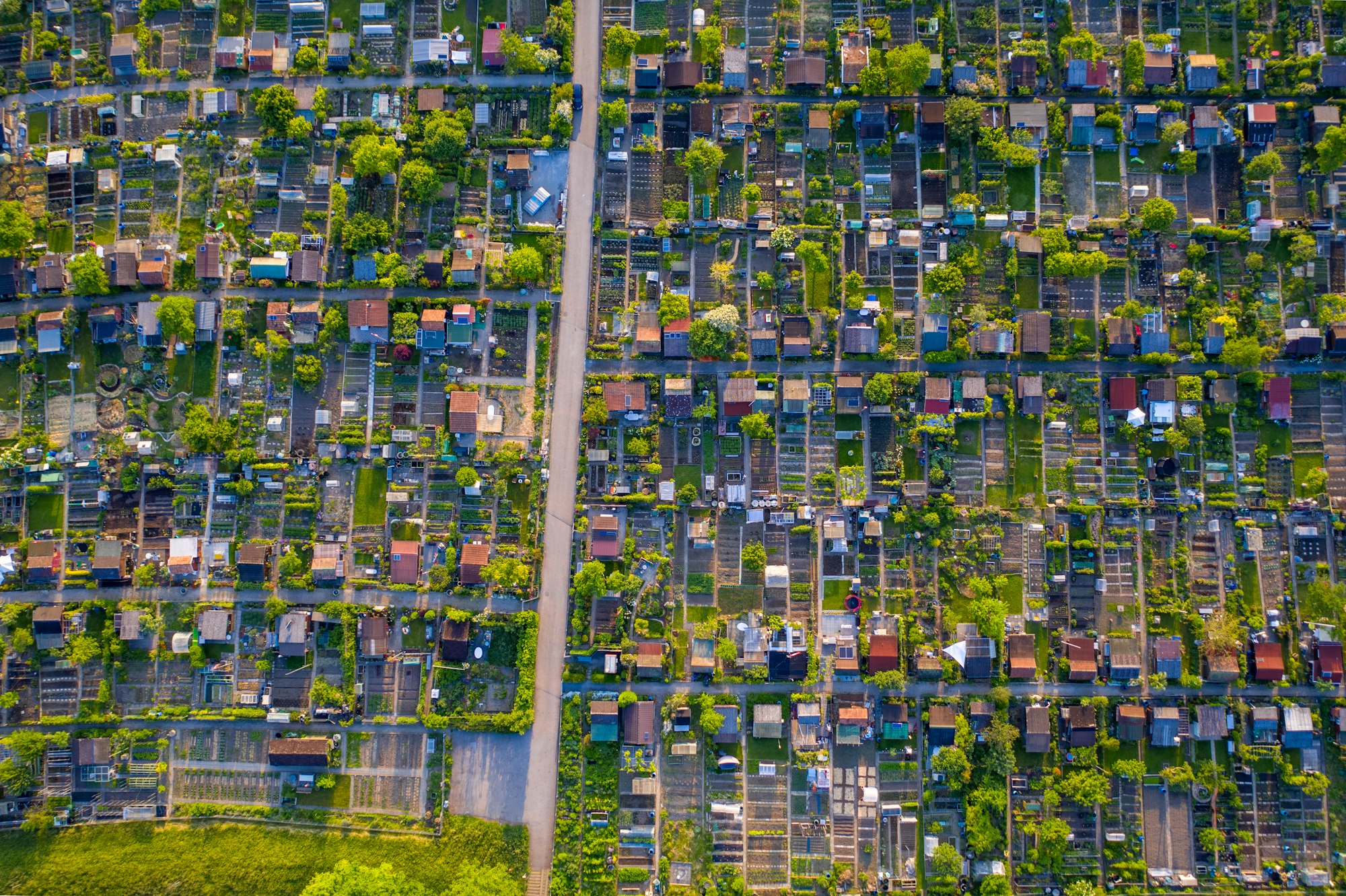

So, what’s gone wrong? A big part of the issue is housing supply. Australia simply hasn’t built enough homes to keep up with demand.

The country lags behind other OECD nations when it comes to homes per capita, and our vacancy rates are scraping the bottom of the barrel. The result? A housing market that’s tight, expensive, and increasingly out of reach for both buyers and renters.

The Australian Government has set an ambitious target: 1.2 million new homes by FY2029 under the National Housing Accord.

But here’s the thing—current forecasts suggest we’ll only hit about 60% of that goal. That means we need an extra 462,000 homes just to catch up.

In this blog post we break down the Property Council of Australia’s report Smarter Incentives, More Homes, which goes deep into why the current incentive program, the New Homes Bonus, is falling short.

More importantly, we’ll discuss what needs to change to truly tackle the housing crisis and make housing affordable for everyday Aussies.

The Scope of the Housing Affordability Crisis

The numbers don’t lie—housing affordability in Australia is a huge problem. Since 2003, property prices have raced far ahead of incomes. Back then, it took around 8.4 years to save for a 20% house deposit. Fast forward to 2023, and it’s ballooned to over 10 years.

This doesn’t just reflect higher prices—it highlights how housing costs have consistently outstripped wage growth.

But it’s not just homeowners feeling the squeeze. Renters are doing it tough too. Nearly half of all low-income households (about 45%) in major cities are in rental stress, spending an unsustainable chunk of their income on rent. And with Australia’s vacancy rate sitting stubbornly below 2%, it’s no wonder. A healthy market needs around 3% vacancy to balance demand and keep prices stable, but we’re nowhere near that.

When you zoom out to a global perspective, it’s clear we’re falling behind. Australia has fewer homes per capita than many other OECD countries.

Plus, with demand rising and supply lagging, it’s little wonder our capital cities rank among the most unaffordable in the world. Sydney, for example, was recently rated the second least affordable city out of 94 global markets.

It’s simple economics: too few homes mean higher prices. And with no real signs of improvement, the situation risks locking out a generation of Australians from home ownership, while forcing renters into increasingly dire financial straits.

Understanding the National Housing Accord and Targets

In response to the housing crisis:

The Australian Government set a bold target: 1.2 million new, well-located homes by FY2029.

This goal, part of the National Housing Accord, is meant to boost supply where it’s needed most—areas with access to transport, services, and jobs.

So far, though, things aren’t looking promising:

Current forecasts suggest Australia will fall short by a staggering 462,000 homes, with only 738,000 likely to be built by 2029.

That’s roughly 60% of the target. Why the shortfall? Several states and territories are struggling to ramp up construction fast enough. NSW, for instance, faces a shortfall of 185,000 homes, while Victoria is expected to fall short by 71,000. Only the ACT is on track to meet its share.

To put this in perspective, these numbers aren’t just about meeting quotas—they translate to real-world consequences. More homes mean less competition, lower rents, and slower house price growth. Conversely, failing to hit these targets will see affordability worsen, with already stressed markets like Sydney and Melbourne bearing the brunt.

The report highlights that “well-located” homes are critical.

These aren’t just any new homes—they’re ones built in areas with existing infrastructure, like schools, transport links, and community amenities. The idea is to avoid urban sprawl while still meeting demand.

The Promise and Pitfalls of the New Homes Bonus

To help meet the National Housing Accord’s ambitious target, the Australian Government introduced the New Homes Bonus—a $3 billion incentive pool designed to reward states and territories that exceed their housing targets.

The idea sounds good on paper: more homes get built, states get a payout, and everyone wins.

But here’s the problem—it’s just not working as intended. The scheme is designed to pay out after FY2029, meaning jurisdictions won’t see a dollar until the end of the program. For state and territory governments facing budget constraints and infrastructure bottlenecks today, that delay makes it nearly impossible to scale up housing delivery now, when it’s needed most.

The threshold to qualify for payments is also too high. Apart from the ACT, no state or territory is currently projected to meet its share of the “well-located” homes target. Victoria, for instance, won’t hit its target until at least 2032, and Queensland, WA, and SA are even further behind. This setup risks turning the entire scheme into a token gesture—big on announcements, light on results.

What’s more, the report highlights a lack of clear targets, transparency, and flexibility in the scheme’s design. Stakeholders have called for upfront payments, more realistic timelines, and better governance to ensure the bonus actually works as an incentive, not a mirage.

Past incentive schemes offer lessons here. Programs like the National Competition Policy and Universal Access to Early Childhood Education worked because they offered clear goals, upfront or staged payments, and ongoing accountability. The New Homes Bonus, in contrast, seems to be missing those critical pieces.

Four Key Recommendations to Improve the New Homes Bonus

The Property Council’s report doesn’t just identify problems—it also lays out four key recommendations to fix the New Homes Bonus and actually deliver the housing Australia needs. Let’s take a look at what they are:

1. Refine the Scheme for Maximum Engagement

The current “wait until it’s done” payment model is a huge roadblock. The report recommends introducing upfront payments to give states the resources they need to start building now, with staged payments tied to milestones along the way. This could come with a “clawback” mechanism—if targets aren’t met, payments can be reduced or reclaimed. Plus, the scheme should be extended to seven years, giving states more time to implement reforms and scale up housing delivery.

2. Increase the Value of the Scheme

The $3 billion pool just isn’t big enough to move the needle. The report suggests doubling it to $6 billion, highlighting the sheer scale of the housing challenge. Any unspent funds should be “ringfenced” (set aside) for future housing initiatives, like infrastructure funding to support new developments. This ensures momentum isn’t lost if immediate targets aren’t fully met.

3. Strengthen Transparency and Governance

At present, progress is hard to track, targets are vague, and there’s no centralised system to measure results. The report calls for a public, easily accessible dashboard tracking state-by-state progress. It also recommends clearer definitions of key terms like “well-located,” and regular reporting and forums to share insights and best practices between jurisdictions.

4. Enhance Federal Leadership

Tackling housing affordability isn’t just a state problem—it’s a national challenge. The report proposes establishing a Housing Sub-Committee of Cabinet to coordinate efforts, pool resources, and align policies. It also encourages the federal government to consider every lever available—from tax reform to planning incentives—to boost housing supply. Collaboration is key.

What This Means for Australian Homeowners and Builders

If the 1.2 million new homes target is met, it could be a game changer for homeowners, renters, and builders alike. Here’s what the report suggests:

✅ Renters could breathe easier. Hitting the housing target could slash rents in well-located areas by up to $90 a week nationwide, with the biggest drops in places like the Northern Territory ($220), NSW ($130), and WA ($100). That’s a huge relief for millions of households.

✅ House price growth could slow down. In areas where the extra homes are built, price rises could flatten out or even drop slightly—especially in the NT (-4.3%), NSW (-1.0%), and Tasmania (-0.8%). This doesn’t mean prices will crash, but it could help cool the market and make ownership more realistic for first-home buyers.

✅ The economy gets a shot in the arm. Building those extra 462,000 homes would inject $128 billion into the economy, with $45 billion in direct construction activity and $83 billion through flow-on effects like jobs in manufacturing, retail, and professional services.

✅ Jobs, jobs, and more jobs. The construction push could support 368,000 full-time equivalent jobs each year, including 55,000 direct roles in residential building, 75,000 in construction services, and 238,000 in other industries. This isn’t just a housing fix—it’s an economic lifeline.

But here's the kicker: without bold reforms, these benefits may never materialise. Does a four-year political term support bold reforms? Do our politicians have the gumption to take action against the wishes of their political donors?

Missed targets mean continued high rents, stubbornly unaffordable housing, and a lost opportunity to boost the economy and create jobs. For homeowners and builders, the stakes are high—and the time to act is now.

Where the Report Might Be Biased or Optimistic

While the Property Council’s report does a great job highlighting the scale of Australia’s housing crisis and the need for smarter incentives, it’s not without its blind spots. Here’s where a critical eye is needed:

🔎 Over-reliance on supply-side solutions. The report leans heavily on the idea that boosting supply will naturally cool prices and rents. While more homes should help, it doesn’t fully consider demand-side factors like investor activity, population growth, or macroeconomic pressures (think interest rates, wage growth, and inflation). Simply building more houses won’t guarantee lower prices if demand keeps rising.

🔎 Optimistic economic forecasts. The projected $128 billion economic boost and 368,000 jobs hinge on stable economic conditions. Global events, inflation spikes, or domestic policy shifts could easily disrupt these assumptions, leaving the construction sector (and the broader economy) more vulnerable than the report suggests.

🔎 Assumptions about state readiness. The report presumes that if the federal government tweaks incentives, state and territory governments will be ready to deliver. But capacity issues—from planning delays to workforce shortages—are already hampering progress. Simply offering more money may not resolve these systemic bottlenecks.

🔎 Limited focus on broader reforms. The report concentrates on the New Homes Bonus and largely sidesteps other levers like tax reforms (e.g., negative gearing, capital gains), infrastructure provision, and workforce development. A holistic approach, not just one scheme, will be essential to address the crisis.

In short, while the report makes a compelling case for reworking the New Homes Bonus, it might be a little too optimistic about what this alone can achieve. A real fix needs a broader, coordinated approach tackling both supply and demand challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ's)

1. What is the National Housing Accord, and how will it affect homeowners?

The National Housing Accord is an agreement to deliver 1.2 million well-located new homes by FY2029. If successful, it could ease rental and house price pressures, offering homeowners and renters more affordable options.

2. How many new homes does Australia need, and why?

Australia needs an extra 462,000 homes above current projections to meet the target. This shortfall reflects years of undersupply and growing demand.

3. Why is the New Homes Bonus seen as ineffective?

The bonus offers payments after FY2029, has a high threshold for success, and lacks upfront funding or clear progress tracking—making it hard for states to engage meaningfully.

4. How would upfront payments and a longer scheme duration help?

Upfront payments and a longer time frame would give states resources and time to implement reforms and scale housing delivery. This approach has worked in past incentive schemes.

5. How much could rents and house prices drop if the target is achieved?

Rents could drop by up to $90 per week nationwide (more in some regions), and house price growth could slow by up to 4.3% annually in areas with the most new housing.

6. Will building more homes alone solve the affordability crisis?

No. While more supply is essential, demand factors (like interest rates and population growth) and broader policies (like tax and planning reform) also play crucial roles.

7. How does this affect first-home buyers in Australia?

If successful, these reforms could reduce entry costs and ease competition for homes. But delays or half-measures mean first-home buyers could still face significant barriers.

8. What role do state and local governments play?

They’re critical. States control planning, approvals, and infrastructure delivery. Without their cooperation, targets will be missed, and affordability won’t improve.

9. What lessons can we learn from past incentive schemes?

Successful schemes offered upfront payments, clear targets, good governance, and accountability. They show that well-designed policies can drive real reform.

10. What can homeowners and builders do to support smarter housing policies?

Stay informed, advocate for policies that balance supply and demand, and push for reforms that make sense—both in the short and long term.

Further Reading

Member discussion