When Housing Isn’t a Safe Place Anymore

When most of us think about disaster preparedness, we think about sandbags, fire evacuation plans, or cyclone warnings. But very few of us think about what happens when the problem isn’t the flood itself — it’s that you have nowhere safe or secure to return to after the water recedes.

In 2024, a national symposium brought together 125 experts from across the housing, homelessness, and emergency management sectors to talk about one of Australia’s most overlooked problems: what happens when our housing system fails during a crisis — not just structurally, but systemically.

The June 2025 final report from that event doesn’t pull any punches. It makes the case that disasters like floods, fires, and cyclones don’t just cause homelessness — they expose the weaknesses we’ve built into our housing system over decades.

The people most affected aren’t always those with insurance policies or rebuilding contracts. They’re often the people already struggling: renters, people in temporary or insecure housing, and those already at risk of homelessness before the storm hit.

In this blog post we break down the key findings of that report, and why they matter for anyone building, renting, or buying a home in Australia.

You don’t need to be an expert in emergency management or social policy to understand why housing fails during disasters — and what can be done about it. You just need to ask the right questions about how we design, deliver, and protect the places we live.

Because the truth is, disasters don’t discriminate — but our systems often do. And when the housing safety net doesn’t hold, the impact isn’t temporary. It’s long-term, and often deeply unequal.

The Report

Disasters Aren’t Natural — But System Failures Are

One of the strongest messages coming out of the 2025 Housing, Homelessness and Disasters report is this: disasters aren’t “natural.” Hazards like bushfires, cyclones, and floods happen — but they only become disasters when they hit people and places that aren’t prepared or protected.

That’s not bad luck. That’s bad planning.

The report echoes the view of the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: building in flood-prone areas, failing to maintain infrastructure, and ignoring the needs of vulnerable communities are all policy choices — not natural phenomena. When we build homes in risky places without proper design standards, or leave renters out of emergency plans, we set the stage for a disaster before the first raindrop falls.

The Australian housing system is already under pressure. With over 640,000 affordable and social homes missing from supply, 32% of renters in housing stress, and public housing waitlists stretching to 169,000 households, there's not much slack in the system. So when a flood or fire hits, there’s nowhere to go. And the people pushed out of their homes — or further away from housing altogether — are often already marginalised.

It gets worse when you look at where we build. Out of Australia’s 10.9 million dwellings:

- 5.6 million are bushfire-prone

- 953,000 are flood-prone

- 17,500 are at risk of coastal erosion

These aren’t theoretical risks. According to the University of Queensland, an average of 23,000 people are displaced by disasters every year, and that number is expected to climb with population growth and climate change.

And yet, our housing responses — both public and private — still treat these events as if they’re unexpected. The building industry talks a lot about resilience, but we still see homes approved in vulnerable areas without meaningful elevation, drainage planning, or climate adaptation features.

The National Construction Code (NCC) does provide minimum performance standards, but it doesn’t stop councils or developers from approving new subdivisions in known hazard zones.

The problem isn’t just that hazards exist — it’s that the systems around land use, housing supply, and disaster response consistently fail to address real-world risk.

What Happens During a Disaster? Lessons From the Front Lines

When disaster hits, the response needs to be fast, coordinated, and inclusive. But as the report shows, the reality in Australia is often patchy, overwhelmed, and inequitable — especially for renters, people in insecure housing, and those already experiencing homelessness.

One of the most important lessons from the Symposium was that disaster recovery isn’t just about clearing roads or restoring power — it’s about housing. And not just for homeowners. Everyone, from those in social housing to people couch-surfing or living in caravans, needs to be included in emergency planning and response.

Take the 2022 Victorian floods as a case in point. Emergency Recovery Victoria (ERV) quickly set up Elmore Village, a temporary housing village built within two weeks of the flood. It housed over 200 residents over nine months — and crucially, it was located within their community. This local response respected social ties and access to services and reflected what the report refers to as a “no wrong door” approach — where no matter which agency someone turns to, they’re connected to the help they need without getting the runaround.

But not all responses are this smooth. The report details common problems:

- Loss of personal documents like IDs or proof of tenancy — making it hard for renters or people experiencing homelessness to qualify for assistance.

- Repeated trauma of having to tell their story again and again to different service providers.

- Overloaded systems with little to no surge capacity — especially in communities where the local homelessness services are already under strain.

One practical solution discussed was the use of centralised, real-time data sharing. During the Victorian floods, Homes Victoria was able to reduce the administrative burden by building off pandemic-era tech systems that allowed agencies to share information. This meant affected people didn’t have to keep retelling their story — or try to dig soggy paperwork out of their collapsed homes.

The importance of governance also came up. When disaster hits, having clear leadership structures and emergency budgets already in place makes a big difference.

During the Lismore floods, for example, pre-allocated trauma-informed services and strong leadership networks were essential in preventing complete collapse of the housing support response.

What Happens Before the Next One? Why Inclusion Starts Early

Preparedness isn’t just about stockpiling sandbags and clearing gutters. It’s about who’s involved in the planning — and who’s left out.

One of the key takeaways from the 2025 report is that people experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity are routinely excluded from disaster planning. That includes:

- People sleeping rough

- People couch surfing

- Families in overcrowded housing

- Residents of caravan parks or informal accommodation

- Renters without formal lease agreements

Why are they overlooked? Because much of our planning is still built around homeowners with fixed addresses. And yet, when disaster hits, these are the people most at risk — and often least able to access help.

The report makes a strong case for embedding lived experience into the planning process. That means not just consulting the same peak bodies every few years, but actually paying people with lived experience to participate in the design of disaster plans. It’s not just about fairness — it results in better, more usable strategies.

Programs like Logan Together and the Person-Centred Emergency Preparedness (P-CEP) framework show what it looks like when communities are part of the planning, not just recipients of it. These models prioritise:

- Psychosocial safety

- Trauma-informed design

- Respectful language (e.g., “people without homes” vs “the homeless”)

- Community cohesion (e.g., gardens, shared activities, and familiar local services)

Participants in the Symposium also flagged the danger of “consultation fatigue” — where multiple agencies ask the same questions over and over, pulling frontline staff away from actual service delivery. It’s a time cost many smaller community organisations can’t afford. One solution? Pay them for their time, streamline the engagement process, and coordinate across government departments.

There was also a strong push to meet people where they are — not just metaphorically, but literally. Services like Ask Izzy (a digital service directory for vulnerable Australians) were praised as practical tools to connect people to real-time support.

Likewise, simple measures like locating support staff in libraries, community centres or even laundromats can make support feel more accessible — and less institutional.

What Happens After? Temporary Housing, Long-Term Pain

The idea of "temporary housing" sounds simple — a stopgap until people can return home. But the report makes it clear: in many parts of Australia, that “temporary” phase drags on for months or even years, especially when housing markets are already broken before the disaster hits.

Disasters don’t just destroy homes — they intensify existing shortages. Emergency shelters fill up fast. Caravan parks often sit on flood-prone land themselves. Hotels and motels are either unavailable or snapped up by recovery workers. That means survivors — renters, families, elderly residents — are now competing with tradies, insurance reps, and government contractors for whatever’s left.

The 2025 report, particularly through the work of Professor John Fien and the Social Recovery Reference Group, highlights that:

Australia’s approach to temporary housing is outdated and underprepared.

The usual cycle — emergency shelter, then short-term leases, then rebuild — isn’t working. There are too many delays, too few options, and not enough support built into the housing solutions themselves.

Key challenges include:

- Delays in insurance payouts

- Slow planning approvals

- Reluctance from banks to lend in high-risk areas

- Underinsurance among low-income residents

- No coordinated pipeline for emergency-to-permanent housing transitions

There are, however, some promising approaches. The report points to innovations like modular housing that can be quickly deployed and later adapted into permanent homes.

There’s a strong argument here for shifting from “replacement” thinking to “resilient recovery” — not just building what was lost, but building better for the next time.

Effective post-disaster housing must go beyond just roofs and walls. It must be:

- Trauma-informed — supporting people dealing with loss, displacement, and mental health stress.

- Flexible — able to accommodate families, individuals with disabilities, and people with complex needs (e.g. hoarding, addiction).

- Integrated — connected to health, social, and community services, ideally through place-based delivery.

One model referenced in the report includes housing pods in the Blue Mountains, designed with community connection, safety, and well-being in mind. Rather than isolating residents, these pods are built with shared spaces and wraparound supports — aiming not just to house people, but to help them recover.

Systemic Failure — When Policy Doesn’t Meet the Ground

If there’s one thread running through the 2025 report, it’s this:

Australia doesn’t have a housing problem because of disasters — we have a disaster problem because of housing.

The real issue isn’t just destroyed properties or uninhabitable rentals. It’s that the policies, funding, and support systems meant to help people recover are disjointed, reactive, and often built around ownership — not need.

Disaster response in Australia still operates with a quiet assumption: if you’re a homeowner, you’re eligible for help. If you’re a renter, in informal housing, or already homeless, things get murky. The system defaults to asset protection. And when the framework is built around property loss, those without assets often lose access to recovery support altogether.

This creates a two-tiered recovery:

- The “deserving” disaster victim: insured, housed, likely to be supported.

- The “undeserving” one: homeless, in unstable housing, or lacking formal tenancy documentation — left to fall through the cracks.

The report is blunt: this is a policy failure.

And it’s one that plays out across all levels of government, often leaving services scrambling to respond without clear guidance, funding, or authority. Housing, homelessness, and emergency response are still treated as separate silos — even though they deal with the same people at the same time.

There are specific groups who bear the brunt of this fragmentation:

- Renters without formal leases

- Caravan park residents on vulnerable land

- Couch surfers who can’t prove previous residence

- Social housing tenants displaced but de-prioritised

- People with disabilities or trauma-related vulnerabilities

- Those already experiencing homelessness

When policy doesn’t recognise these groups in its definitions, it doesn’t build responses that meet their needs.

The Symposium calls for a National Disaster Housing and Homelessness Framework to align these sectors — so housing support, mental health, tenancy protections, and disaster funding don’t operate like a game of pass-the-parcel. The proposed framework includes:

- Coordinated national strategy

- Cross-sector taskforce

- Recognition of renters and homeless individuals in disaster planning

- Investment in modular housing and temporary options

- Inclusion of people with lived experience in disaster reviews

And importantly, the report highlights the need for clear governance, data-sharing protocols, and pre-planned budgeting.

Because when systems don’t talk to each other, people fall through the cracks — especially when they’ve lost everything.

This section is where the report feels the most grounded — and the most urgent. Because while temporary housing and recovery services matter, they’ll always fall short if the system treating disaster like an “event” keeps ignoring the ongoing housing crisis underneath it.

Big Ideas for a Broken System – What the Symposium Wants to See

While much of the report diagnoses where Australia is going wrong, this section sets out what it believes could go right — if we choose to change direction. The Symposium didn’t just identify problems; it laid out a road map of reforms that could help stop housing from becoming a disaster in the first place.

At the heart of the recommendations is the call to break down silos — bringing together housing, homelessness, emergency response, planning, climate risk, and social support into a single coordinated approach. Right now, each sector operates independently, even though their work overlaps completely during and after disasters.

👉️ The report makes six major recommendations:

1. Create a National Disaster Housing and Homelessness Framework

This isn’t just a plan on paper — it’s a full rethink of how Australia deals with housing during crises. It proposes:

- A national task force spanning government, NGOs, and community leaders.

- Alignment of housing, disaster, and homelessness policy under one umbrella.

- Planning that includes renters, social housing tenants, rough sleepers, and informal housing occupants from the start.

- Real investment in modular, mobile, and community-based housing as scalable responses.

- Formalising partnerships so response agencies and housing providers can act fast, not scramble.

2. Build Disaster Resilience Into the National Housing Plan

If resilience is the goal, then it has to be part of the broader housing strategy — not an afterthought.

- Integrate with the National Climate Adaptation Plan and new land-use and building codes under development.

- Incorporate pre-disaster housing strategies, including transitional and long-term planning.

- Invest in new social and affordable housing — not just any housing, but climate-resilient, accessible, and culturally appropriate housing for groups often left behind, like First Nations people and people with disabilities.

3. Use Better Data to Plan Better Housing

You can’t fix what you don’t understand.

- Pre-map land availability for temporary housing before disaster hits.

- Share data across local, state, and federal government to speed up recovery.

- Fund local governments to implement disaster-resilient housing programs — including through existing funds like the Disaster Ready Fund.

- Strengthen tenancy protections and minimum housing standards, so renters are not living in flood-prone sheds or fire traps.

4. Strengthen Housing Recovery Processes

Right now, there’s no consistent method for housing recovery across states and agencies. The report proposes:

- Clear frameworks that include all housing types — not just owner-occupied.

- Tying together housing, mental health, and social supports in the recovery phase.

- Joint training and simulation across sectors, so services are ready to coordinate under pressure.

- Including lived experience voices in post-disaster reviews — because planning without users is just theory.

5. Expand Access to Local Support Services

This is where the response touches the ground. The report calls for:

- Integrated hubs with housing, health, and social services in one location.

- Expanded outreach teams to go where people are — particularly those in insecure or informal housing.

- “No wrong door” policies that stop people being bounced between disconnected services.

- Trauma-informed training for all recovery workers, and long-term funding for services so support doesn’t vanish after the media attention fades.

6. Keep the Momentum Going

- Annual follow-up symposium

- Ongoing cross-sector collaboration

- Advocacy for continued investment in disaster-resilient housing — not just grants after the fact, but strategic, permanent funding built into housing policy.

Together, these aren’t small tweaks. They are a complete rethink of how Australia prepares for and responds to disasters through the lens of housing. But they’re not unattainable — many of them already exist in pockets.

Where the Report Feels Optimistic — and Where It Feels Biased

The 2025 Housing, Homelessness and Disasters report is one of the more honest government-supported documents you’ll come across. It doesn’t sugar-coat the failings of Australia’s housing system in times of crisis,

and it’s refreshingly candid in acknowledging that many of these “disasters” are man-made — or at least made worse by inaction, bad planning, or fractured systems.

It’s especially strong in three areas:

- Humanising vulnerability: The report consistently centres people, not just infrastructure. It doesn’t talk about “the homeless” as an abstract group — it talks about real people in caravans, couch surfing, or in insecure rentals who are pushed into crisis when disaster hits.

- Systemic clarity: It draws a clean line between housing insecurity and disaster vulnerability. Poor-quality housing, rental stress, and lack of affordable options all increase disaster risk — not just in the moment, but in recovery.

- Emphasis on trauma-informed and community-based responses: The examples of Elmore Village, modular pods in the Blue Mountains, and integrated service hubs are practical, achievable, and scalable. These aren't moonshot ideas — they’re things already working in isolated places that just need political will and investment to go national.

But the report does have blind spots — or at least some gaps in emphasis that readers should be aware of.

1. Light on accountability for private industry

The building industry, insurance sector, and developers are barely mentioned. There’s no meaningful discussion about:

- Why we keep allowing developers to build in flood-prone or bushfire-prone areas.

- Why certifiers, builders, or private landlords aren’t held to higher post-disaster standards.

- 👉️ The role of insurers in delaying recovery through slow payouts or exclusions that leave renters and low-income owners without support.

In reality, many post-disaster failures stem not just from government inaction but from the way private companies shift risk onto households — often without warning, consent, or consequences.

2. Over reliance on top-down solutions

While the report makes a strong case for cross-sector collaboration, many of the proposed reforms hinge on new frameworks, national strategies, or expanded agency roles. That’s good — but it assumes government will act in good faith and execute these plans effectively. Given what we've seen after past disasters, that’s not always a safe bet.

What’s missing is a more detailed look at accountability — what happens when these frameworks fail or when funding gets delayed? Who gets to hold departments, councils, or ministers to account?

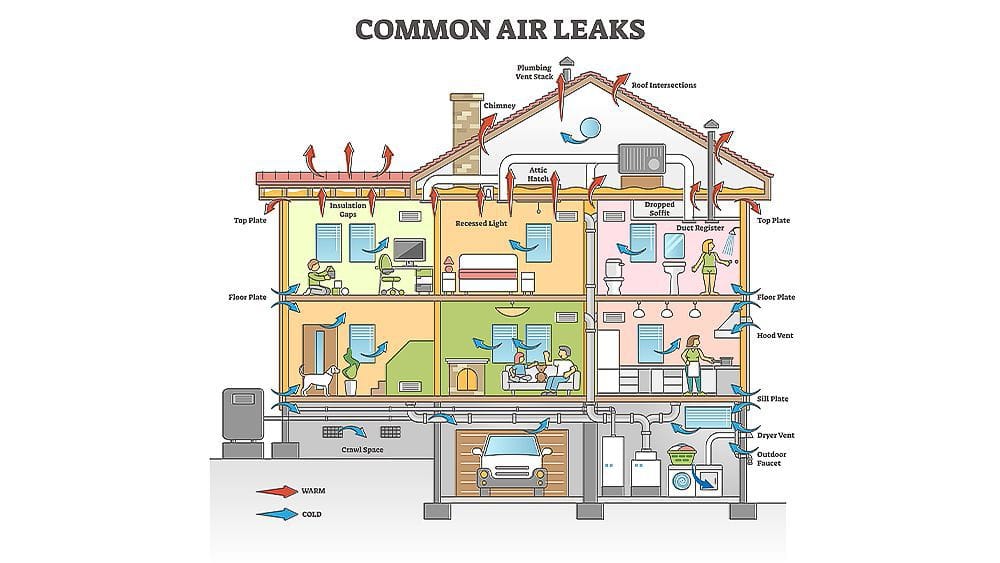

3. Limited discussion of building codes and retrofitting

Given that so much of Australia’s housing stock is vulnerable by design (e.g. slab-on-ground homes in flood zones, or fibro houses without bush fire protections), the lack of deep engagement with the National Construction Code (NCC) is surprising.

There’s also no detailed call for retrofitting existing homes to better withstand disasters — a major oversight given the scale of the risk.

4. No mention of class action potential or legal remedy

For residents who are displaced by policy or regulatory failures (e.g. approvals for subdivisions on floodplains), there’s no discussion of compensation frameworks or legal remedies. This absence further suggests the report still leans toward policy optimism over legal realism.

Final Thoughts – What This Means for Your Home

If there’s one message homeowners and future home builders should take from this report, it’s this:

👉️ Disasters don’t cause homelessness or housing stress on their own. They expose the weaknesses in our housing system that were already there — unaffordable rents, poorly built homes, planning decisions made without proper risk assessment, and emergency responses that exclude those without property deeds.

If you’re building a home in Australia today, you need to be thinking beyond layout and finishes. You need to ask:

- Is this site prone to flooding, bushfires, or erosion?

- Has the home been designed to meet or exceed the National Construction Code (NCC) requirements for resilience?

- What protections do I have as a renter, buyer, or investor if a disaster hits?

- How well is the local council prepared for future emergencies?

- Is this a home I can safely stay in — or evacuate from — if the worst happens?

You also need to remember that the biggest risk to your housing security might not come from the weather — it might come from slow insurance payouts, weak tenancy protections, or recovery funding that prioritises owners over renters.

For builders, designers, certifiers, and developers, the implications are just as serious. If you’re not building with future risk in mind, you’re part of the problem — and eventually, your clients will pay the price.

What the 2025 report makes clear is that safe housing is not just about materials and methods. It’s about whether people — especially those most vulnerable — are protected by the systems we build around housing. And right now, those systems are full of holes.

Fixing that starts with acknowledging the gaps. Then filling them — not after the next disaster, but before.

🔍 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does the report mean when it says “disasters aren’t natural”?

It means that while hazards like floods and fires are natural, the impacts they cause — like homelessness and housing loss — are shaped by human decisions. Poor planning, unsafe building locations, and weak support systems turn hazards into disasters.

2. I’m a renter — am I eligible for help after a disaster?

Yes, but it depends on the state or territory and whether you’re formally listed on a lease. Unfortunately, renters are often overlooked in disaster recovery policies that prioritise homeowners. The report calls for this to change.

3. What is a “no wrong door” approach?

It’s a service model where people can go to any agency or support service and get help — without being bounced around or turned away because “it’s not their job.” It aims to reduce red tape and stress during a crisis.

4. What’s being done to improve emergency housing?

The report recommends more investment in modular and mobile housing options that can be deployed quickly, along with place-based support services that include trauma-informed care, health, and housing workers.

5. Why do housing costs go up after a disaster?

Disasters increase demand for local housing — not just from residents who’ve lost homes, but from recovery workers, insurers, and trades. This pushes up rents and reduces availability, especially in already tight markets.

6. Is there any support for people who were already homeless before the disaster?

There should be, but in many cases, people experiencing homelessness are excluded from formal recovery support. The report recommends direct outreach, inclusion in planning, and integrated service hubs to fix this gap.

7. What are trauma-informed housing responses?

These are responses that recognise the emotional and psychological effects of disaster and displacement. It includes providing stable, safe housing, minimising stress, avoiding re-traumatisation, and offering onsite mental health support.

8. What can homeowners do to reduce their risk?

Start by checking your property’s risk profile (e.g., bushfire, flood, erosion). Build or retrofit to exceed minimum NCC standards. Ask questions during land selection, and ensure you have adequate insurance and a personal emergency plan.

9. What role do councils and local governments play?

Local governments approve developments, manage planning overlays, and coordinate emergency responses. The report calls on them to better integrate disaster risk into housing approvals and to work with state and federal agencies on recovery.

10. How does this affect people building a new home?

New home builders need to understand that resilience is part of good design. Choose land carefully, review zoning and flood/fire overlays, and engage builders who understand climate-resilient construction. It’s about protecting your investment — and your safety.

Further Reading

PS: Quality Management Checklist Access

All our published checklists are available to download via the Checklists Link in the navigation menu or directly at https://www.constructor.net.au/checklists/.

Please note: You’ll need to be a member and to log in to access the content.

This is necessary to protect our work from being scraped by AI bots, which are currently unregulated and contributing to one of the largest instances of intellectual property theft in history. These checklists represent nearly two years of effort to input and format, and we want to ensure they are used responsibly.

All of this unwanted, automated nonsense consumes bandwidth, slows down page speed, and clogs up the internet—while the companies behind it profit, harvest our data, and sell it back to us with a smug look of superiority on their faces.

Member discussion