What this report is, and why it matters

Each year the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) takes the pulse of Australia’s housing market. The State of the Housing System 2025 is their latest check-up—handed to the Housing Minister in April 2025—and it lays out how prices, rents, and supply are tracking.

The report feeds into the National Housing Accord, a deal between governments and industry aiming for 1.2 million new homes between 2024 and 2029. At 240,000 homes a year, it’s deliberately ambitious—more than business as usual, but similar to past construction peaks. The idea is to keep governments and builders accountable.

The 2024 snapshot: prices, rents, affordability, and supply gap

The report shows that 2024 was another tough year for both buyers and renters. National dwelling prices increased by 4.9% over the year, with a further 0.7% rise in the March quarter of 2025. Advertised rents followed a similar path, lifting 4.8% in 2024 and 1.7% in early 2025. While slower than the spikes of 2022–23, the pressure on households has not gone away.

Affordability worsened

On average, a new mortgage in 2024 required almost 50% of the median household income, while a new lease consumed about one-third.

The time needed to save a deposit stretched to 10.6 years, and the national price-to-income ratio reached 8.0, the highest on record.

Supply fell short

Only 177,000 new homes were completed in 2024, compared with an estimated underlying demand of 223,000. Detached houses still made up the majority, but higher-density completions fell back to around 65,000, underlining the weakness in apartment and townhouse supply.

Vacancy rates offered little relief

Nationally, vacancies sat at 1.8% at the end of 2024, still well below the 2.5% generally seen as a balanced rental market. In practice, this means competition for rentals remains strong and renters continue to face higher stress.

Outlook to 2029: what the Council expects

Looking ahead, the report makes it clear that Australia is unlikely to hit the National Housing Accord target of 1.2 million homes by June 2029. The Council’s modelling forecasts around 938,000 gross completions over the five-year period—an average of 188,000 per year.

After accounting for demolitions (about 113,000 homes), the net addition falls to roughly 825,000 dwellings. Against expected demand of about 904,000 new households forming in the same period, this leaves a shortfall of around 79,000 homes by 2029.

Affordability is expected to “stabilise” but not improve substantially.

- The price-to-income ratio is projected to ease slightly, from 8.0 in 2024 down to 7.7 by 2029.

- Rent growth is forecast to slow to below 4% per year by 2027, though vacancy rates are expected to remain under 2.5%, which is still considered tight.

- Mortgage repayments as a share of income may plateau but remain high, leaving many buyers stretched.

Performance will differ by state

👉️ None are projected to meet their full share of the 1.2 million target. Victoria is closest, reaching 98% of its implied share, while Queensland sits at 79%, and New South Wales at only 65%.

Detached housing is expected to remain dominant, making up just under two-thirds of completions. Higher-density housing, which could deliver large numbers in urban areas, is likely to remain constrained due to feasibility and financing challenges.

The Council also cautions that forecasts depend on assumptions holding steady. Shifts in interest rates, construction costs, or broader economic shocks could quickly change the trajectory.

What’s holding back supply: materials, labour, finance, feasibility

The report makes it clear that the shortage of homes isn’t just about demand—it’s about blockages on the supply side. Several factors are slowing delivery:

Materials:

Construction costs remain stubbornly high, even though the pace of price growth eased in 2024. Building input prices rose 1.6% overall, but with big differences between categories. Steel and timber fell slightly (-3.7% and -3.2%), while electrical items and concrete products climbed (+6.0% and +5.2%). For builders and homeowners, this means quotes may stabilise, but not necessarily fall.

Labour:

Skilled trades are still in short supply. The HIA Trades Availability Index stayed in negative territory through 2024, showing ongoing shortages. Bricklayers, tilers, roofers, and carpenters were the hardest to find. While shortages are easing slightly, the pool of skilled workers remains too shallow to support higher levels of construction.

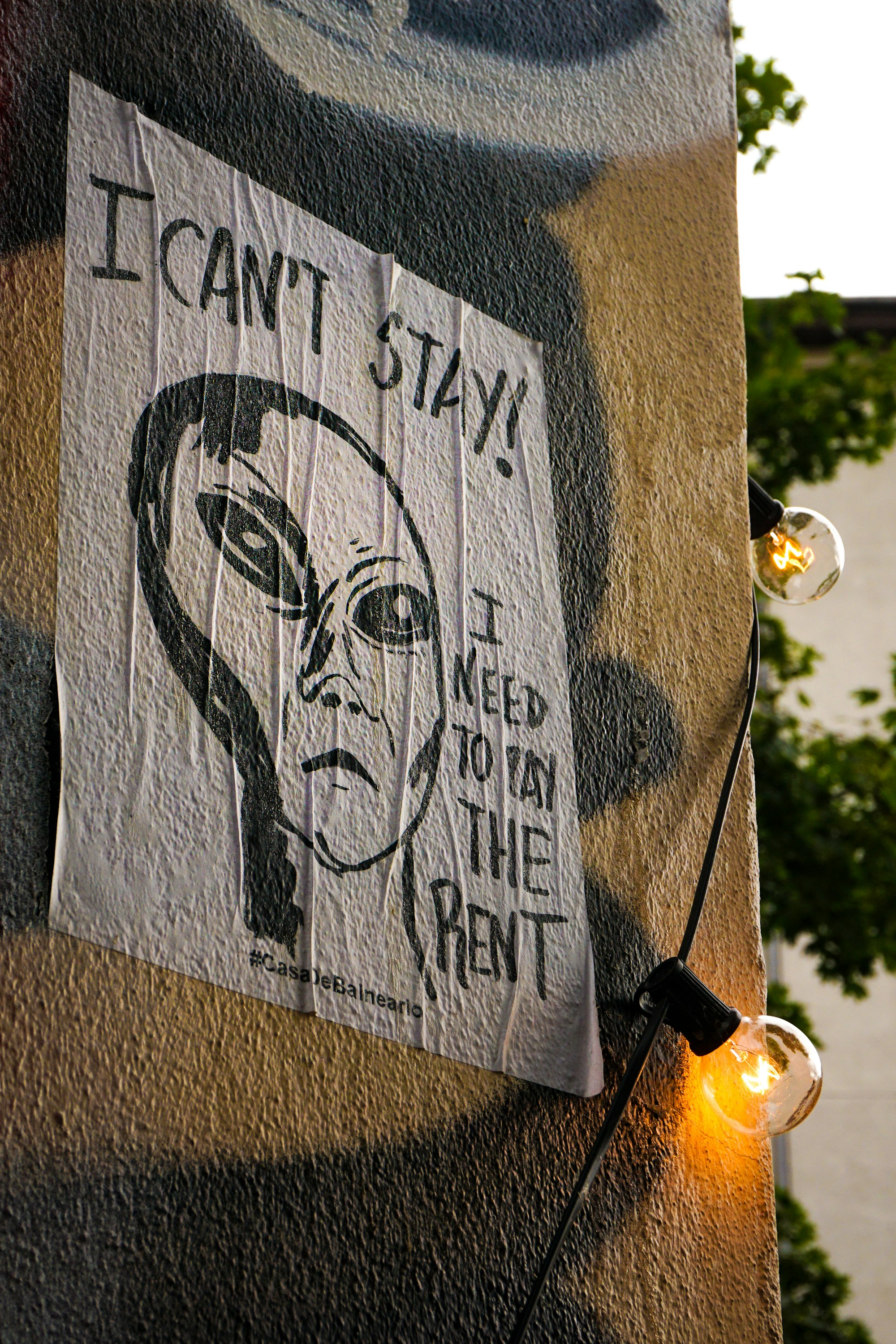

This was from 2014 - so we're flush with bricklaying labour now, right?

Finance and feasibility:

Apartment and townhouse projects face tough conditions. Lenders require high levels of pre-sales before financing, but buyers are wary due to costs and delays. Feasibility is also a hurdle—rising land, construction, and compliance costs mean many projects simply don’t stack up, particularly in the mid-rise apartment market across major capitals.

Approvals and commencements:

Planning approvals and project commencements remain subdued, especially in higher-density housing. Even if conditions improve, it takes time for approvals to flow through to completions.

Renovations vs. new builds:

Renovations now account for about 40% of residential activity. While this keeps trades busy, it doesn’t add to the overall housing stock—so the supply gap remains.

Planning and land release: where approvals can speed up

The report highlights that even when builders and trades are ready, the planning system can hold projects back.

Inconsistent rules, long approval times, and unclear processes make it harder to get new housing underway.

National alignment:

These ideas link with the National Planning Reform Blueprint and the example of the NSW Housing Delivery Authority, which is designed to speed up assessments and land release.

Encouraging more density:

The report stresses the importance of the “missing middle”—townhouses, terraces, and smaller apartment blocks—not just high-rise towers. These medium-density options can add homes quickly in well-located suburbs without relying on very large developments.

What this means for homeowners:

For anyone planning a build or renovation, the local planning rules in your council area matter. Objective standards and “deemed-to-comply” pathways can make approvals smoother and less costly. On the other hand, vague or subjective rules create uncertainty and delays that add directly to holding costs.

Renters, social and affordable housing

The report stresses that rental stress remains widespread, especially among lower-income households. More than half of low-income renters are in stress—defined as spending over 30% of their income on housing—and many remain in that situation for long periods. The Council links this persistence to poorer health, education, and well being outcomes.

Rent assistance and CPI rents

The Federal Government’s boost to Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) in 2023–24 helped dampen measured rent growth. CPI rents rose 6.4% in 2024, but without the CRA increase, the rise would have been closer to 7.8%. This shows how policy support can make a difference, but also highlights how fragile affordability remains.

Social housing

The stock of social housing has grown slightly in raw numbers but continues to fall as a share of the total housing system. Waiting lists remain close to record highs, and a growing proportion of applicants are classified as being in “greatest need”.

New commitments

Through the Housing Accord period, the Australian Government has committed to funding at least 55,000 new social and affordable homes, with states and territories promising an additional 25,000 publicly funded dwellings. While significant, this is still a fraction of the overall shortfall.

Rental policy stance

The Council supports a “Better Deal for Renters” program that introduces stronger protections and minimum standards. However, it does not support rent freezes, warning they would reduce incentives for investment and could make supply even tighter in the long run.

Why this matters to you

Even if you’re not renting yourself, rental stress affects the wider system. Tight rental markets push more households to try buying, adding pressure to prices. For landlords, expect greater scrutiny of property standards and compliance with tenancy laws.

Quality, safety, sustainability, and compliance

The report doesn’t just measure how many homes are being built—it also looks at whether they are safe, durable, and built to standard.

Quality matters because defects and poor performance add long-term costs for owners, renters, and governments.

Defects and structural issues

The Council highlights that renters and public housing tenants are more likely to report major structural problems compared with owner-occupiers. This points to a gap in the consistency of construction quality, especially in lower-cost segments.

Energy performance

The Council proposes setting a long-term target where all new homes meet or exceed a 7-star NatHERS rating. This aligns with the National Construction Code (NCC), which already requires 7 stars as the minimum energy efficiency standard in most jurisdictions (with some transitional arrangements still in place).

For homeowners, this means design decisions around glazing, insulation, orientation, and services are more important than ever.

Safety and resilience

Natural hazards like bushfire, flood, and extreme heat are becoming more prominent risks. The report notes that homes need to be “safe and sustainable” across their full lifecycle. This links back to durability provisions in the NCC and Australian Standards, which specify minimum requirements for structural adequacy, fire resistance, and weatherproofing.

Why this matters for homeowners

Meeting NCC minimums is only the start. The quality of workmanship, choice of materials, and compliance checks along the way determine whether your home performs as intended.

Where the report may be biased or limited

While it provides fantastic data, it’s important to understand where the conclusions may lean or where gaps exist.

Target setting and measurement

The report apportions the 1.2 million Accord target to states and territories based on their population share in December 2022. This approach is transparent, but it doesn’t account for future population growth, migration flows, or housing needs that differ by region. In practice, this can advantage slower-growing states and disadvantage faster-growing ones.

Forecast reliability

The Council acknowledges its forecasts are most reliable in the short term. Longer-term predictions depend on relationships between interest rates, construction costs, and demand behaving as they have in the past—something that is far from guaranteed. This means the “outlook to 2029” should be read as indicative, not certain.

Emphasis on supply-side solutions

The recommendations lean heavily towards unlocking more supply through planning reform, productivity gains, and incentives for building. While these are essential, there is less emphasis on managing demand drivers—such as tax settings or the speculative use of housing as an asset—which also shape affordability (interpretive observation).

Data gaps

The report also notes that definitions of “affordable housing” differ between governments, making it difficult to measure outcomes consistently. This inconsistency makes comparisons less reliable across jurisdictions.

Rents: two different stories

The distinction between advertised rents (which reflect current market conditions) and CPI rents (which include existing leases and are influenced by Rent Assistance) can create confusion. Depending on which measure is used, rental affordability may appear better or worse.

State snapshot: Queensland focus

Queensland’s housing story looks slightly better than some states, but it still falls well short of what’s needed.

Meeting targets

Queensland is forecast to deliver about 79% of its share of the 1.2 million Accord homes. That’s stronger than New South Wales (65%), but it still leaves a significant shortfall compared with demand.

Rental affordability

Regional Queensland stands out as one of the least affordable rental markets in the country. In many areas, households spend more than a third of their income on rent—well above the stress threshold.

Supply mix

Like elsewhere, detached homes dominate completions, while higher-density projects are constrained by cost and feasibility challenges. For South East Queensland in particular, this means growth continues to push outward into fringe suburbs, while infill opportunities in established areas remain under-supplied.

Implications for homeowners

For buyers and builders in Queensland, these conditions translate into strong competition for trades, longer approval times in growth corridors, and ongoing pressure on rents.

Practical steps for homeowners and prospective owners

The report paints a big-picture view of housing pressures, but what can individual homeowners or buyers actually do in response?

Here are some practical steps drawn from the findings

Budget with buffers

Material and labour costs remain volatile. While some inputs like timber and steel have eased, others (like electrical and concrete products) continue to climb. Allow for contingencies in your budget so unexpected changes don’t derail your project.

Check builder capacity

Labour shortages are improving only slowly, especially in trades like bricklaying, tiling, and roofing. Before committing, ask prospective builders about their current pipeline and whether they have the resources to complete your job on time.

Plan approvals strategically

Where possible, aim for “deemed-to-comply” or objective approval pathways in your local council. These are designed to be faster, clearer, and less prone to subjective delays.

Design for compliance and performance

Factor NCC requirements into your plans from the outset. A 7-star NatHERS rating is now the minimum standard in most jurisdictions, affecting decisions on orientation, glazing, and insulation. Going beyond the minimum can mean lower energy bills and a more resilient home.

Think about the after-tax position

The Council’s call for tax reform is a reminder that housing decisions are shaped by incentives. Before subdividing, developing, or adding an investment property, work out the after-tax outcome—not just the construction costs.

🙈 What to watch next: signals homeowners can track

The report points to markers that indicate how housing conditions may shift. For homeowners and prospective buyers, keeping an eye on these signals can help anticipate changes.

👉️ Approvals and commencements

These are the leading indicators of future supply. The report shows approvals remain weak, particularly for higher-density housing. If approval volumes start lifting, it could signal easing pressure in the pipeline a year or two down the track.

👉️ Vacancy rates

National vacancy is still around 1.8%, below the 2.5% level generally considered balanced. Any move closer to 2.5% would suggest rental competition is easing; a fall would point to renewed rental stress.

👉️ Rent trends

Rent growth is forecast to slow to under 4% per year by 2027. Watching how actual increases compare with forecasts will reveal whether affordability is improving or slipping further.

👉️ Material and labour costs

While overall building input prices only rose 1.6% in 2024, components are moving differently—steel and timber down, but electrical and concrete up. These shifts directly affect quotes and timelines for homeowners.

👉️ Policy and reform progress

The Council emphasises planning reform, tax settings, and rental protections as key levers. Following state government announcements on these fronts gives early warning of cost or compliance changes

FAQs – Common Questions About the 2025 Housing Report

1. Is the government really going to deliver 1.2 million new homes by 2029?

Unlikely. The Council forecasts about 938,000 gross completions, or 825,000 after demolitions. That leaves a shortfall of around 79,000 homes by June 2029.

2. What does this mean for affordability?

Conditions may “stabilise” but not improve much. Price-to-income is expected to ease only slightly (from 8.0 down to 7.7), and rents are still forecast to grow by up to 4% a year by 2027.

3. Why are advertised rents and CPI rents different?

Advertised rents track new listings. CPI rents include existing leases and are affected by Rent Assistance. In 2024, CPI rents rose 6.4%, but advertised rents were up 4.8%.

4. What’s the biggest bottleneck for new homes?

Higher-density projects. Apartments and townhouses are slowed by finance, feasibility, and planning hurdles. Detached homes are still being built, but not fast enough to close the gap.

5. How long does it now take to save for a deposit?

On average, 10.6 years—a record high. Rising prices relative to incomes are the main reason.

6. What vacancy rate means balance in the rental market?

About 2.5%. Australia ended 2024 at 1.8%, which means the market remains tight.

7. What’s happening with social and affordable housing?

The government has promised at least 55,000 new social and affordable homes, plus 25,000 from the states during the Accord period. But demand still far exceeds supply.

8. How do tax policies affect the housing system?

Negative gearing, capital gains tax discounts, and stamp duty all shape buying and selling behaviour. The Council calls for a review of these settings.

9. Is Queensland doing any better?

Queensland is on track to deliver 79% of its share of the Accord homes—better than NSW but still a shortfall. Regional QLD also has some of the least affordable rents in the country.

10. What can homeowners do to reduce risks in this environment?

Plan early, build in budget buffers, choose efficient approval pathways, design for NCC compliance, and always check the after-tax position before investing or subdividing.

Further Reading

Member discussion