Introduction

So far in this series, we’ve seen the theme play out: your data became something to buy and sell, AI supercharged its value, and the incentives behind it all keep bending the way you experience the internet.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal was a wake-up call. It showed how something as simple as personality clues and social connections could be turned into tools for political influence on a massive scale. And it wasn’t a one-off—it was a glimpse of a business model already in motion.

In this post, we take a step back to name the model and unpack how it works. Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff calls it surveillance capitalism—an economy that treats human experience as raw material for prediction and profit.

In her research, she explains how extracting behavioural data, selling predictions in what she calls ‘behavioural futures markets,’ and normalising subtle behaviour-shaping has changed more than just technology. It’s also shifted the very terms of personal freedom and democratic life.

If that sounds weird, the dictionary defines surveillance capitalisim as:

‘private companies monitor people to accumulate data for profit.’

That’s what’s really going on behind those friendly feeds and ‘personalised’ recommendations. The real question isn’t whether your data gets collected—it does.

The question is whether all that tracking and nudging works for you… or just for them

Generative AI changes the game. Instead of only predicting what you’ll click, it can spin up the content itself—made to grab your attention and watch how you respond. That’s why experts worry it could lock in the worst parts of the attention economy: prediction and manipulation, all rolled into one, and much harder to spot.

This isn’t about shaming you for using today’s tech. It’s about showing you the trade-offs hiding in plain sight. By the end, ‘free’ won’t feel like a bargain—it’ll look more like a bill you’re paying in a different currency: your behaviour.

Surveillance Capitalism: When Life Becomes the Business Model

Surveillance capitalism’ might sound like something "academic", but the idea is pretty simple. It’s an economic system that treats your life—what you do, say, and even feel—as raw material. Companies scoop up that data, run it through their systems, and turn it into predictions about your future. Those predictions are then sold to whoever’s paying to influence your next move.

Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff, who coined the term, calls surveillance capitalism a ‘new economic order.’ In her view, your private experiences are scooped up and turned into something she calls behavioural futures markets—places where predictions about what you’ll buy, click, or believe are traded like stocks. You’re not the customer anymore—you’re the raw material input!

This is nothing like old-school ads either. Billboards and TV reached everyone with the same message. Now, every ad can be different—tailored to when you’re most vulnerable to spending. Google and Meta don’t just show ads; they auction off your attention. In 2023, Alphabet made over $230 billion from it.

It doesn’t stop at shopping either. Cambridge Analytica proved that. Ordinary likes and shares on Facebook were turned into psychological profiles and then weaponised in political campaigns. It was surveillance capitalism in action.

The tech has only gotten sharper. AI now reads your moods, gauges your attention, and adjusts what you see instantly. One Harvard scholar summed it up: this business model doesn’t just shape markets—it chips away at democracy itself.

Trust AI? Or 'Trust No One'?

Gracious and humble—for one night only. A pathological display cloaked in superiority and condescension. The ethics box was ticked here, never to be checked again: ‘I gave you your chance to ask, now it’s over. This is preformative art to a public audience.

The paradox between being CEO yet reminding the audience to "trust no one" perhaps to intend to appear humble while still reinforcing power (flexing).

Truly, he is a Renaissance man at heart, torn between duty and humility. In the history books, will he be seen as humble, savvy, both… or neither?

👇️ Gotta love that margin loan and higher company valuations!

"But I’ve Got Nothing to Hide…” Why Privacy Still Matters

Whenever the topic of data privacy comes up, someone always says: “I’ve got nothing to hide, so why should I care?” On the surface, this sounds reasonable. If you’re not doing anything wrong, why worry about who’s watching?

The flaw in this logic is that privacy isn’t about hiding—it’s about control.

Privacy is the ability to decide who knows what about you, and under what circumstances.

Daniel Solove (LINK), a legal scholar on privacy, puts it bluntly: the “nothing to hide” argument misses the point because privacy protects more than just secrets; it protects autonomy, dignity, and freedom of expression.

Think of it this another way: you close the curtains at night, not because you’re doing something scandalous, but because your home life is yours. You lock your phone, not because it’s full of crimes, but because it’s full of conversations, contacts, and context that others could misuse.

And misuse is the key word here. Consumer data isn’t just collected—it’s used to predict, shape, and sometimes manipulate behaviour. Cambridge Analytica showed how ordinary Facebook likes could be turned into political tools. Meta’s leaked internal studies revealed how Instagram’s engagement-driven feeds harmed teenagers’ mental health. These aren’t examples of hidden crimes being exposed—they’re examples of everyday data being weaponised against the very people who provided it.

There’s also a power imbalance. Corporations don’t just gather data; they hoard it, analyse it, and use it in ways consumers can’t see or contest. As Zuboff argues, this isn’t about secrecy—it’s about asymmetry. Companies know far more about you than you know about them, and that imbalance translates into power.

What’s wild is that the evidence is already on the table. Study after study shows the harm—proof that social media was built to exploit human psychology, to hook us with likes, clicks, and dopamine spikes, all to fatten the bottom line of the companies behind it.

If this were any other consumer product causing this level of damage, it would be banned, pulled from shelves, and the makers fined into oblivion.

Yet here we are, letting these platforms creep deeper into our lives, deliberately tweaked to demand more of our time, more of our attention, and more of ourselves.

And now along comes ‘AI’—pitched as the future—with the same companies telling us to swallow it whole. Forget the harms we already know and accept as fact.

Just take your medicine, hand over more of your data, and trust them to use it wisely. The marketing machine is in overdrive, insisting that ‘life with AI will be better.’ Better for who? The only guaranteed improvement is shareholder value for the companies selling us AI—the new social media, only on steroids

The Monetisation Loop: How Data Becomes Behaviour

If surveillance capitalism is the business model, then the monetisation loop is the engine under the hood. It’s not about collecting your data once and cashing in. It’s a cycle—one that picks up speed the more you click, scroll, and engage.

It all starts with extraction. Every digital move you make leaves a mark—how long you hover over a post, when you swipe past a video, or what time of night you tend to shop. Harvard’s Shoshana Zuboff calls this ‘behavioural surplus’—extra data gathered not to run the service, but to feed the prediction machine.

Next comes analysis. This is where AI shines, turning your scattered clicks and pauses into neat patterns. Stay glued to beach photos every winter? The system knows you’re ripe for travel ads when it’s cold. Doomscroll at night?

Expect offers for quick fixes when you’re tired and less guarded. These patterns don’t just explain you—they predict you.

Those predictions don’t sit idle—they’re sold. Zuboff calls this the ‘behavioural futures market.’ Google and Meta auction off their guesses about you in milliseconds on ad exchanges. The more accurate the prediction, the higher your value. Just look at Google’s books: in 2023, its ad arm pulled in hundreds of billions of dollars, making up the bulk of its profits (SOURCE).

The loop doesn’t end with prediction. Next comes influence. Once the system knows when you’ll act, it nudges you—through ads, recommendations, or content. Soon it’s not just predicting behaviour. It’s writing it.

We’ve already seen this in the wild. Remember Pokémon Go in 2016? On the surface it was a fun game, but under the hood it showed how nudges could be monetised. Players were steered toward certain spots—often sponsored businesses that paid for the foot traffic. What felt like play was also a commercial loop where your attention was for sale.

Generative AI takes the loop even further. It’s no longer just curating content—it can create it on the spot. Stories, images, even conversations are tailored to your past behaviour. As researchers warn, generative AI makes the line between recommendation and manipulation even blurrier—while creating more opportunities to monetise your attention.

The monetisation loop, then, isn’t neutral. It’s not just passively recording what you do; it’s actively adjusting the environment to increase the chance of a profitable outcome.

Real-World Consequences: When Prediction Becomes Power

It’s easy to think of surveillance capitalism as something abstract—humming away in data centres and boardrooms far from everyday life. But its fingerprints are everywhere, often in ways we hardly notice.

Politics is one of the clearest examples. Cambridge Analytica showed how harvested Facebook data could be weaponised during Brexit and the 2016 U.S. election.

Millions of profiles were mined to find which emotional buttons worked on which voters (SOURCE). The aim wasn’t to persuade everyone—it was to nudge the right people at the right time. But once politics becomes hyper-personalised, citizens no longer share the same facts, and the democratic public square starts to crack.

Now think about mental health. Meta’s own leaked research, reported by The Wall Street Journal in 2021, showed Instagram was making life worse for many teenagers—especially girls—by fuelling body image anxiety and depression. The algorithm wasn’t designed to hurt, but it was built to maximise attention. And in that loop, more attention meant more profit—even if it came at a heavy human cost.

Even day-to-day consumer life is touched by this. Dynamic pricing—where algorithms tweak costs based on your profile—is already here (see the video below for more on this). Ride-hailing apps surge prices during bad weather or train delays. Online shops may quietly adjust prices depending on your browsing history or even the device you’re using. The ‘invisible hand’ of the market? Here it looks more like a personalised script, written by algorithms designed to squeeze maximum value from you.

What links all these cases is the move from watching to steering. Once every flicker of attention is tracked and turned into predictions, the obvious next step is to use those predictions to push you in certain directions. The loss isn’t just privacy—it’s autonomy. Your choices still feel free, but they’re being quietly shaped for someone else’s profit.

Conclusion: From Awareness to Agency

In this series, we’ve gone from scandals to systems. We started with how data profiling crept in, then saw how algorithms scaled it, and how AI made influence faster and sharper. This post steps back and puts a name to it all: surveillance capitalism.

This isn’t just about banner ads or pop-ups. It’s about an economy where your attention, habits, and even moods get packaged and sold. As Zuboff points out, the real danger isn’t just that your data is collected—it’s that it feeds markets trading in predictions about you, with the power to quietly reshape what you do

This doesn’t mean you need to ditch your phone or swear off the internet. But it does mean that ‘free’ usually isn’t. When a service costs nothing, you’re often paying with something more valuable—your future choices. Seeing that trade-off is the first step to taking control.

There are alternatives. Europe has started pushing back with rules like GDPR and the AI Act. Tools like Brave or Signal show that services can work without strip-mining your data.

And more and more people are asking for transparency—proof that users aren’t as passive as the system assumes.

The thread through all four posts? Autonomy. Who decides what you see and do—you, or shareholders?

👉️ The more you see the system, the harder it is for your choices to be quietly outsourced.

FAQ

1. What does “surveillance capitalism” actually mean?

It’s the business model where companies treat your actions, habits, and even emotions as raw material. They analyse that data to predict what you’ll do next and sell those predictions to advertisers, political groups, or others who want to influence you.

2. How is this different from old advertising?

Traditional ads were the same for everyone. Surveillance capitalism makes ads (and recommendations) personal, based on detailed profiles built from your digital life.

3. Where does AI fit into this?

AI supercharges the process. It finds patterns in your behaviour, predicts your future actions, and increasingly creates tailored content to keep your attention.

4. Is my data really that valuable?

Yes. Alphabet (Google’s parent company) earned more than $230 billion in advertising revenue in 2023, largely from behavioural data.

5. What are the biggest risks to me?

The main concern isn’t embarrassment—it’s autonomy. When your choices are constantly nudged for profit, you lose some ability to decide freely.

6. Has this affected politics?

Absolutely. Cambridge Analytica showed how harvested data could target voters with messages tailored to their fears and hopes, affecting elections and referendums.

7. What about mental health?

Internal research leaked from Meta revealed Instagram could harm teens’ mental health by reinforcing negative body image through algorithm-driven feeds.

8. Can anything be done to stop this?

Yes, but it’s tricky. Regulations like GDPR and the EU’s AI Act aim to rein in harmful practices. On a personal level, using privacy-first tools (like encrypted messaging or privacy-focused browsers) helps limit exposure.

Further Reading + Sources + References

From Instagram’s Toll on Teens to Unmoderated ‘Elite’ Users, Here’s a Break Down of the Wall Street Journal’s Facebook Revelations - LINK

TikTok knew depth of app’s risks to children, court document alleges - SOURCE

Reuters: Google, Character.AI must face lawsuit over teen’s death - LINK

Reuters: Facebook must face DC attorney general’s lawsuit tied to Cambridge Analytica scandal - LINK

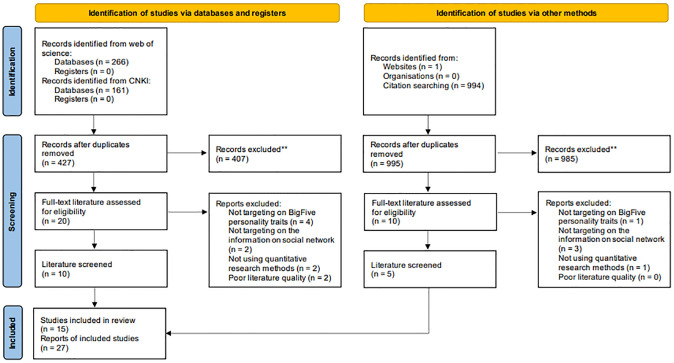

👉️ Social Media and the Big Five: A Review of Literature - LINK

👉️ Social profiling through image understanding: Personality inference using convolutional neural networks - LINK

✅ Want to learn how to update your privacy settings?

Naomi Brockwell’s NBTV YouTube channel features great explainers that are clear and easy to understand.

Or, if you’d like to dive a bit deeper into the tech side—without going overboard—check out this channel.