Why This Report Matters

Back in 2018, the Building Ministers’ Forum (BMF) commissioned Professor Peter Shergold and lawyer Bronwyn Weir to take a hard look at Australia’s building regulation system.

Their task? To find out whether the National Construction Code (NCC) was being properly enforced and whether the public could have confidence in the buildings being delivered across the country.

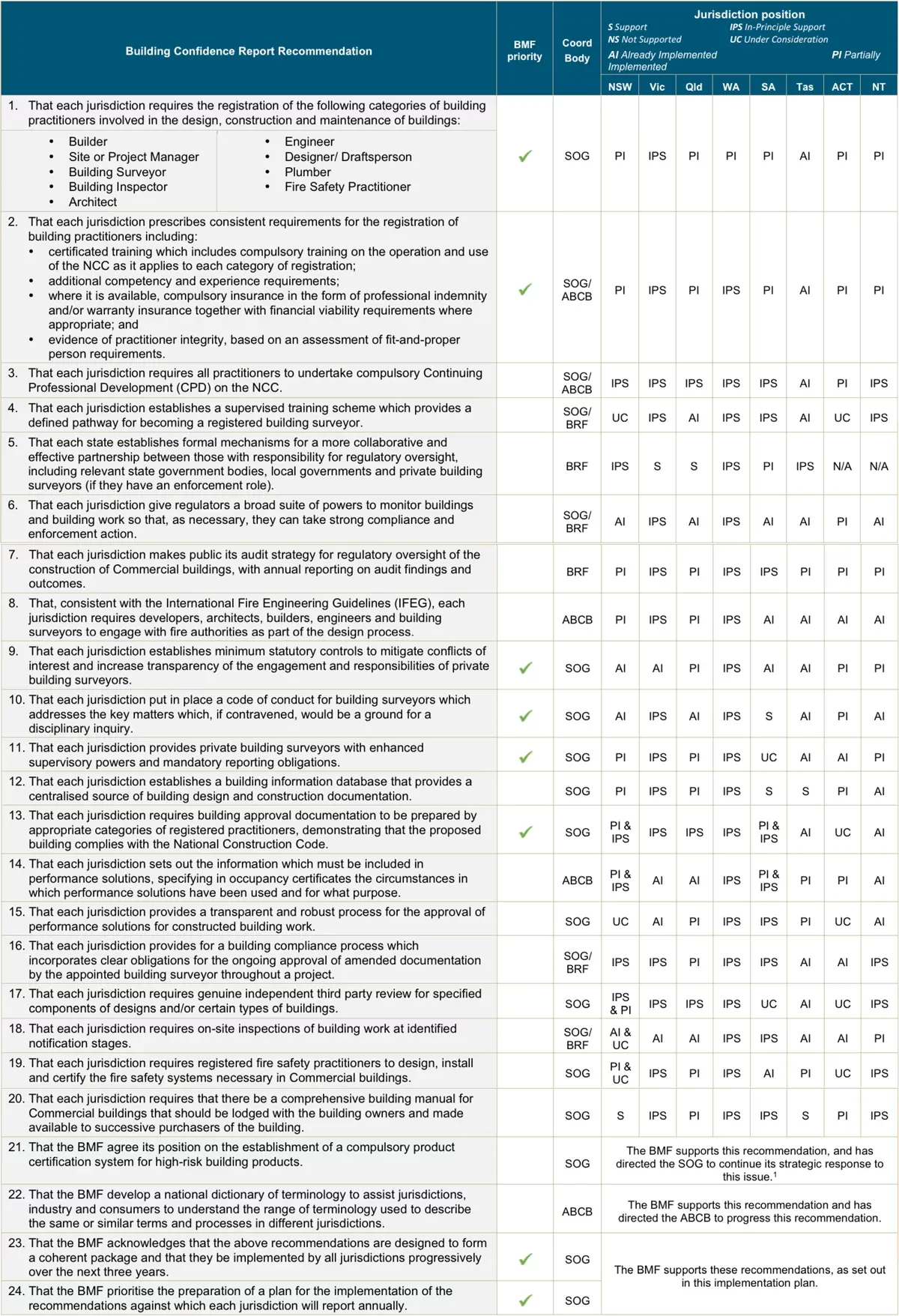

The result was the Building Confidence report—24 recommendations designed to fix weaknesses in compliance and enforcement. At its core, the report wasn’t about rewriting the NCC itself (which already sets minimum standards for safety, health, and amenity). Instead, it was about whether those standards were actually being applied on the ground—and the answer wasn’t encouraging.

Shergold and Weir found serious cracks in the system:

- Poor compliance and oversight meant buildings were going up with safety risks, from flammable cladding to weak roof structures.

- Inconsistent registration and training left many practitioners without the skills or knowledge to properly apply the NCC.

- Fragmented enforcement saw responsibilities spread across multiple regulators, private certifiers, and councils—often leading to confusion, duplication, or simply no action.

- Weak accountability meant that when things went wrong, homeowners often bore the costs.

The big picture? Unless governments, regulators, and industry worked together to lift standards, public confidence in the safety and quality of Australian buildings would keep sliding.

The report’s central message was simple but direct:

the NCC only works if everyone can trust it’s enforced properly.

That means stronger oversight, clearer accountability, and better transparency at every stage of design, approval, and construction.

When you hear about “building standards,” remember—it’s not just about what’s written in the code. It’s about how well those standards are applied and enforced.

What the Review Looked At

Shergold and Weir weren’t given free rein to overhaul the entire building system. They were given very specific instructions—the Terms of Reference. These spelled out exactly what the Building Ministers’ Forum wanted assessed:

- Roles and responsibilities of everyone involved—from builders and designers to certifiers, engineers, and regulators.

- Training and licensing: how qualifications were set, whether continuing professional development (CPD) existed, and whether practitioners were up to date with the National Construction Code (NCC).

- Documentation: whether design and construction paperwork was clear, complete, and available for checking.

- Inspection regimes: how often inspections were happening and who was doing them.

- Audit and enforcement powers: what regulators could (and couldn’t) do to stop dodgy work.

- Building products: how compliant or safe they were, and how to stop non-conforming products from slipping through.

In other words, the review zoomed in on the plumbing of the system—not the code itself, but how it was being applied in the real world.

To build their recommendations, Shergold and Weir spoke to a wide range of stakeholders. They held over 50 meetings with regulators, governments, and industry groups, and received a dozen written submissions.

That mix gave them a decent picture of how the system operated, though you could argue it leaned more towards industry and regulators than everyday consumers. Homeowners—the ones left footing the bill for defects—weren’t really at the centre of the consultation.

This is an important detail. It means the report is practical and technically grounded, but sometimes light on the “lived experience” of people dealing with leaky balconies, fire-safety defects, or endless rectification battles.

The NCC – Performance-Based, Not a Recipe Book

One of the biggest sources of confusion for homeowners is the National Construction Code (NCC). Many people assume it’s a giant recipe book: follow step A, then step B, then step C, and you’ll end up with a compliant home.

That’s not how it works.

The NCC is performance-based. It sets out the outcomes a building must achieve—things like fire safety, structural stability, energy efficiency, and basic amenity. But it doesn’t always tell builders exactly how to achieve those outcomes.

There are two main ways to show compliance:

- Deemed-to-Satisfy (DTS) solutions – the “default recipes” in the code. If your builder follows these, compliance is straightforward.

- Performance Solutions – alternative methods that demonstrate compliance through testing, modelling, or expert judgement. These can be perfectly legitimate, but they rely heavily on documentation, review, and trust in the process.

For homeowners, this flexibility cuts both ways:

- The good news is that it allows for innovation—better materials, creative designs, and sometimes cheaper solutions.

- The bad news is that it opens the door to shortcuts or inconsistent interpretations if compliance isn’t checked rigorously.

This is exactly why Shergold and Weir hammered home the need for stronger documentation and more robust review of performance solutions. A performance solution isn’t the problem in itself—it’s the lack of clear, transparent evidence that the solution actually meets the NCC’s performance requirements.

The key takeaway?

The NCC sets the goalposts. The system of approvals, documentation, and inspections is supposed to prove the ball actually went through them.

Without that proof, you’re left taking someone’s word for it—and that’s not good enough when you’re investing in a home.

Registration and Training – Competence Upfront

Shergold and Weir started their recommendations with the basics: making sure the people working on your home actually know what they’re doing. Sounds obvious, right? But across Australia, qualifications, licensing, and ongoing training were all over the place.

Here’s what they recommended:

- Nationally consistent registration categories: Whether you’re in Queensland or Victoria, a building surveyor (or certifier) should be registered against the same set of categories. That means fewer gaps and less confusion about what people are legally allowed to do.

- Mandatory continuing professional development (CPD): Everyone involved in design, approvals, or certification should keep learning. And not just anything—specific NCC-related hours, so they’re up to date with the rules they’re meant to enforce.

- Stronger pathways into the profession: The report flagged building surveyors in particular. With fewer people entering the profession, workloads were too high, and oversight was being stretched thin. The recommendation? Make the role more attractive and better supported.

- Fit-for-purpose licensing: Builders, engineers, designers, and surveyors should only be doing the work they’re licensed and qualified for—not stretching into areas they don’t fully understand.

For homeowners, this matters because poor training or unclear registration doesn’t just lead to technical mistakes—it leads to compliance failures you might not discover until years later (like waterproofing defects or inadequate fire separation). By the time you do, fixing them can cost tens of thousands of dollars, and the people responsible might have long moved on.

Shergold and Weir’s message was clear: if the people at the start of the process aren’t competent and accountable, the rest of the system is playing catch-up.

Regulators and Audits – More Eyes on the Job

One of the biggest issues Shergold and Weir identified was that regulators often weren’t doing enough checking. In some cases, their powers were limited. In others, they simply weren’t proactive—waiting for complaints instead of actively auditing projects.

Their recommendations were designed to flip that around:

- Stronger regulator powers: State and territory regulators should be able to investigate, enforce, and penalise non-compliance, without being hamstrung by weak legislation.

- Proactive audits: Regulators shouldn’t wait for problems to blow up (think cladding crises or widespread waterproofing failures). They should regularly audit building approvals, inspections, and certifications before issues become disasters.

- Collaboration across jurisdictions: Instead of each state or council running its own show, regulators should work together, sharing data and strategies.

For homeowners, the impact is straightforward: more oversight means less chance of dodgy work slipping through the cracks. But this also comes with a catch—regulators can only do their job well if governments properly resource them. Without enough inspectors, auditors, and enforcement officers, recommendations on paper don’t mean much on the ground.

And while this section of the report focused heavily on commercial and multi-residential buildings (like apartments), the cultural shift flows down to detached houses too. A regulator that enforces standards across the board sets expectations for all builders—big or small.

Fire Authorities in Design – Getting Experts In Early

One of the more specific recommendations from Shergold and Weir was about fire safety performance solutions. In simple terms, these are alternative ways of meeting the NCC’s fire safety requirements—things like evacuation routes, sprinkler systems, or smoke control measures—that don’t always follow the “default” path in the code.

The problem? Too often, these solutions were being designed, signed off, and built without enough independent scrutiny. That left room for risky interpretations, which in turn left occupants exposed.

Shergold and Weir’s fix was straightforward:

- Whenever a performance solution touches fire safety, fire authorities must be involved early in the design process.

- This isn’t about rubber-stamping plans after they’re done—it’s about experts shaping the design from the start, reducing the chance of costly disputes later.

- They pointed to the International Fire Engineering Guidelines as the benchmark for how this engagement should happen.

For homeowners in apartments or multi-storey buildings, this is a big deal. Fire safety is one of those things you can’t afford to discover is inadequate when it’s too late. Involving fire authorities early doesn’t just tick a compliance box—it can save lives.

For detached houses, this recommendation is less direct, but the principle still applies: when specialists are brought in early, designs are safer and more reliable. It’s about getting the right people at the table, not leaving it to chance.

Data and Transparency – Keeping Records Accessible

Another gap Shergold and Weir identified was the lack of reliable, centralised building records.

Too often, approvals, inspection reports, or product certificates were scattered across different offices—or worse, went missing altogether once a project was complete.

Their recommendation was simple but on point in our opinion:

- Create central databases in each jurisdiction that hold all building documentation.

- Ensure searchable, digital access for authorised parties, including owners and future buyers.

- Make information sharing between states, councils, and regulators routine, not optional.

Imagine buying a home and not being able to find proof of past approvals, or discovering that inspection records don’t exist. That uncertainty isn’t just stressful—it can also reduce resale value and make it harder to prove compliance if issues arise.

With transparent, centralised records, you’d have a clear, digital paper trail of your home’s history—approvals, inspections, certifications, and product documentation all in one place. It’s the kind of system that protects buyers, sellers, and even insurers.

But there’s a catch: many states are still building these systems, and rollout is uneven. That means homeowners need to take the lead in keeping their own documentation safe in the meantime.

Documentation & Performance Solutions – Proof, Not Promises

One of the strongest themes in the Shergold–Weir report is:

that good documentation is the backbone of compliance.

Without clear, complete, and accurate paperwork, it’s nearly impossible to check whether a building actually meets the National Construction Code (NCC).

The review found big disparities:

- Designs that didn’t clearly show how compliance was achieved.

- Performance solutions approved with little explanation or supporting evidence.

- Records scattered—or never kept at all—making it hard to track what was actually built.

- Changes made late in the design or construction process with no proper audit trail.

👉️ To fix this, Shergold and Weir recommended:

- A statutory duty on designers to prepare documentation that demonstrates, not just claims, NCC compliance.

- Stronger third-party reviews of performance solutions before they’re approved.

- Mandatory record-keeping: every approval, variation, and solution must be documented and retained.

- Clear approval processes for variations and performance-based approaches, so there’s no grey area.

Why this matters for you:

Without documentation, you have no proof that your home was built to code. That’s not just a compliance risk—it’s a financial one. Missing or weak documentation can affect resale value, insurance, and your ability to enforce warranties.

Think of it this way: if your builder says, “Don’t worry, it complies,” the right answer is, “Great—show me how, and let’s put it on record. in writing, with documentation.”

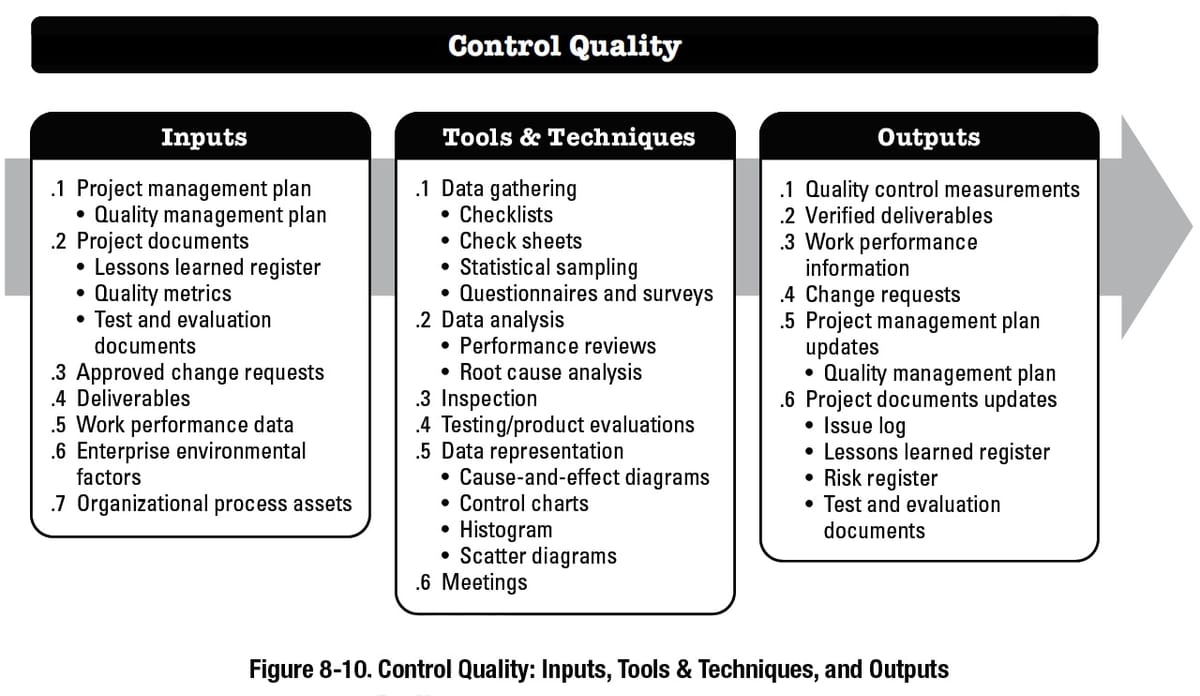

Inspections & Fire Systems – Seeing is Believing

Shergold and Weir didn’t mince their words: too many buildings were being signed off without enough eyes on the work. Once walls are lined or ceilings go in, it’s often too late to spot serious defects.

👉️ They recommended:

- On-site inspections for all building work: not just “tick and flick” paperwork, but actual staged inspections of the structure, waterproofing, fire separation, and services before they’re covered up.

- Stronger oversight of fire safety systems in commercial and multi-residential buildings (like apartments). This means not only checking the installation but also ensuring systems are properly commissioned, tested, and certified before people move in.

For detached homes, this means having every stage checked—from the slab and frame through to waterproofing and fit-off. For apartments, it’s about knowing that critical life-safety systems (sprinklers, alarms, smoke control) have been signed off with evidence, not assumptions.

👉️ Why does this matter? Because inspections catch what documentation alone can’t. Paperwork may say “AS 3740 waterproofing installed,” but only an inspection proves the membrane was actually applied correctly before tiles go down.

It’s also about trust. Regular inspections send a clear message: someone independent is checking that the builder’s promises match what’s happening on site.

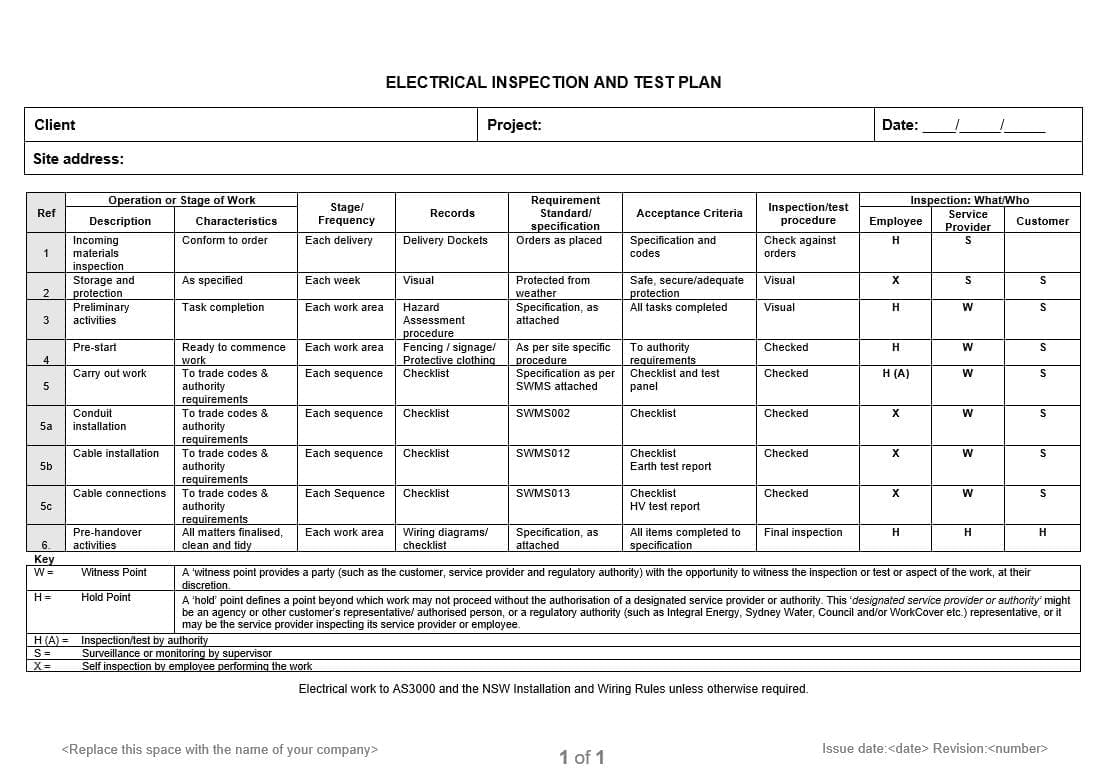

Make sure it includes who attends, what’s being inspected, and what records (photos, signed checklists, certificates) you’ll receive at each stage. Do they require ITPs from trades and suppliers? If not why not?

Keep every record in your project file—you’ll thank yourself later.

📑 Building Manuals – More Than Just a Handover Pack

One of the more forward-looking recommendations in the Shergold–Weir report was the idea of a building manual. This wasn’t aimed at detached houses so much as apartments and larger buildings (Class 2–9), but the principle is worth paying attention to no matter what you’re building or buying.

The problem identified was simple: once a building was finished, owners and managers were often left in the dark. Essential information—like as-built drawings, fire system specifications, or maintenance requirements—was either missing, scattered across consultants, or handed over in a way that made it nearly useless.

👉️ The solution? Require developers to provide a digital building manual that:

- Pulls together all “as-built” documentation.

- Clearly explains fire safety systems and their maintenance needs.

- Stays with the building, so future owners and managers aren’t left guessing.

For apartment owners and body corporates, this is super helpful. A proper building manual means you can manage safety systems much more easily, keep maintenance on schedule, and prove compliance when regulators or insurers or unit owners come calling with pitch forks 👨🌾 (personal experiences mentioned here).

For homeowners in detached houses, you may not get a formal “manual,” but the idea still applies. Having your own organised set of plans, certificates, and product warranties is the residential version of the same safeguard.

It’s about making sure information isn’t lost once the builder walks away.

🤷♂️ This means that as a builder, you can't just chuck everything into a kitchen drawer—toss in the window and door keys, the garage remotes on top—and then fling it open, pointing inside as you demand your final payment. You need to get organised and deliver a finished product, not just a collection of parts.

For house owners, the responsibility is on you. Create your own home manual by compiling all essential documents—as-built plans, warranties, approvals, and inspection reports—in one secure place. Think of it as your home's passport; every journey (like maintenance or a renovation) is smoother with the right paperwork.

Without this documentation, even simple tasks become frustratingly difficult. It's like building a complex IKEA flat-pack without the instructions: you're guaranteed to have parts left over, and the whole process is far more stressful than it needs to be.

Product Safety – Stopping Dangerous Materials at the Door

Australia has had more than its fair share of scandals with dodgy building products—flammable cladding, faulty insulation, and imported materials that don’t meet local standards.

Shergold and Weir called this out directly, warning that non-conforming and non-compliant products were a major weak point in the system.

Their recommendation? A compulsory certification system for high-risk building products. Instead of relying on manufacturer claims and inconsistent checks, there would be a national framework to prove that critical products—like fire-resistant cladding, waterproofing membranes, insulation, and structural fixings—are safe and NCC-compliant before they hit the site.

For homeowners, this is super important:

- Using unsafe products can lead to massive rectification bills (often dumped on owners, not builders or suppliers).

- Insurance and resale value take a hit if your home is found to contain non-compliant products.

- Most importantly, your family’s safety could be compromised.

Until such a certification system is fully in place, homeowners need to stay alert and informed.

You don’t need to know every Australian Standard, but you should expect your builder to provide evidence of product compliance—and be wary if they can’t.

Don’t accept vague assurances; insist on test reports, certificates, or CodeMark documentation. If it’s not documented, it’s not proven. If its not proven, its not insurable!

Implementation, Timing & Terminology – The Long Road to Change

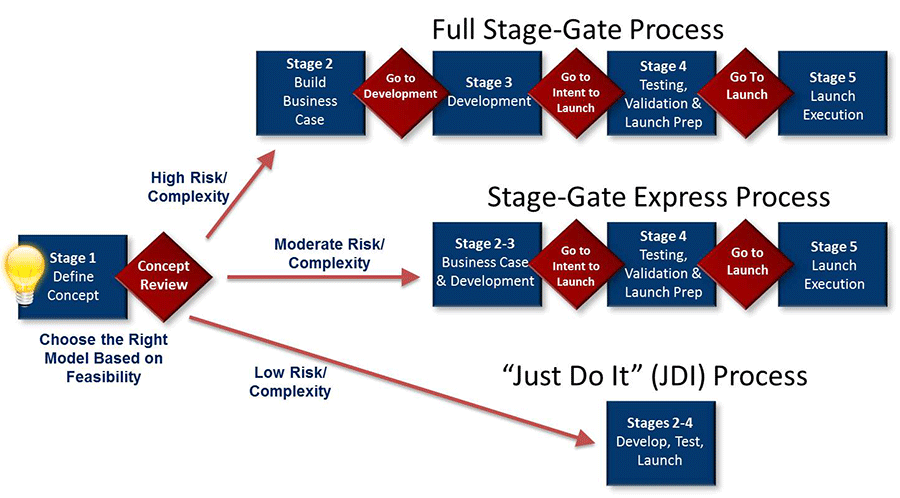

Shergold and Weir didn’t pretend their recommendations could be switched on overnight.

👉️ They set out a three-year timetable for implementation, with each state and territory expected to publicly report on progress each year.

The idea was to give governments, regulators, and industry enough time to adjust while keeping the public informed about what had actually been delivered.

They also called for:

- Annual public reporting by every jurisdiction, so homeowners could see whether reforms were being followed through.

- A national terminology dictionary for building regulation, to cut down on confusion where different states used different terms for the same thing.

- A staged approach to implementation—acknowledging that some reforms, like registration changes, could roll out faster than others, such as new inspection regimes.

For homeowners, this means reform is a slow bum (yes, a deliberate typo to see if your still reading). Some improvements (like better documentation and inspection expectations) can be adopted now, even before governments catch up. Others, like product certification schemes or fully digital record systems, will take time.

The bigger message is this: it wont happen overnight, but it will happen. You can’t assume the system has already fixed itself—you need to stay proactive and apply the these reforms to your own project.

What the Report Doesn’t Do – Bias and Blind Spots

For all its strengths, the Shergold–Weir report wasn’t perfect. It was never designed to be. Its scope was tightly defined, and that shaped what it could—and couldn’t—say.

🙈 Here are the key blind spots and limitations:

- No change to the NCC itself: The report wasn’t about rewriting the National Construction Code. That meant deeper questions about whether the NCC’s requirements are strong enough were left untouched.

- Incremental reform, not a reset: The recommendations tightened guardrails (especially around surveyors and inspections) but kept the private certification model intact. For some critics, that was too cautious.

- Light on consumer voices: Most consultations were with governments, regulators, and industry. Homeowners—the people who live with defects and pay the bills—weren’t the main focus.

- Slow timeline: With a three-year rollout, owners facing current defects were left waiting while systems caught up. For those already caught in costly disputes, “reform on paper” was little comfort.

- Federated compromise: By aiming for a national framework, the recommendations leaned toward “lowest common denominator” solutions. That makes them politically achievable, but sometimes less ambitious than they could be.

The bias here isn’t about bad faith—it’s about the reality of policy-making. The report prioritised what governments and regulators could realistically deliver, not necessarily what homeowners most needed right away.

That’s why taking matters into your own hands—by demanding documentation, independent inspections, and proof of compliance—is so important. In the words of Agent Mulder: trust no one. But more importantly, trust your inner Mulder.

Class 1 Houses vs Class 2 Apartments – Why It Matters

Not all buildings are treated the same under the National Construction Code (NCC). The Shergold–Weir report uses the code’s classification system to separate where reforms matter most.

- Class 1 buildings: Detached houses and townhouses.

- Class 2 buildings: Apartments.

- Class 10 buildings: Non-habitable structures like sheds, garages, and pools.

- Classes 3–9: Larger buildings such as aged care, hospitals, schools, and offices (covered under the “Commercial” umbrella in the report).

Here’s the key difference for homeowners:

- If you’re building a house (Class 1): The most relevant recommendations are those about documentation, staged inspections, surveyor integrity, and product compliance (Recs 9–11, 13–18, 21). These directly affect the quality and safety of the home you live in.

- If you’re buying an apartment (Class 2): In addition to the above, several reforms matter even more—like early fire authority involvement (Rec 8), certification of fire safety systems (Rec 19), and building manuals (Rec 20). These are critical in multi-storey living where fire safety and ongoing maintenance affect everyone in the building.

Why does this distinction matter?

Because you don’t want to be asking for the wrong things.

A detached home doesn’t need a building manual, but it absolutely needs a clear design variations log and thorough inspection records. An apartment, on the other hand, should have both—plus evidence that fire systems were commissioned and approved properly.

The job of a homeowner or buyer is to know which questions apply to their project.

Conclusion: The Homeowner Action List – Your One-Page Safeguard

The Shergold–Weir report may feel like it’s aimed at regulators and industry, but there’s plenty you can take from it right now. Here’s a homeowner’s version—your personal action list to protect your build.

Before you sign a contract

- Confirm your building’s class (house, townhouse, or apartment).

- Appoint a certifier or surveyor who provides a written conflict-of-interest declaration (Recs 9–11).

- Ask your designer for a compliance summary that shows which NCC requirements your design meets and how (Recs 13–17).

During construction

- Agree on a stage-by-stage inspection plan and get inspection reports, not just verbal sign-offs (Rec 18).

- Keep a Design Variations Log—any changes must be documented and approved against the NCC.

- Ask for evidence of product compliance—certificates for waterproofing membranes, insulation, cladding, and fire-resistant materials (Rec 21).

At handover

- For houses: collect as-builts, approvals, inspection reports, and product warranties.

- For apartments: request the building manual (Rec 20), which should include fire safety system details and maintenance requirements.

- Make sure all test and commissioning certificates (fire, electrical, plumbing) are included in your handover pack.

Think of this as your Owner’s Dossier—a complete record of your home from start to finish. It not only protects you now, it also supports resale value and insurance down the track.

Plain-English Glossary Of The Shergold Weir Report

The Shergold–Weir report is full of acronyms and technical terms. Here’s a quick guide so you’re not left scratching your head:

- NCC (National Construction Code): Australia’s building rulebook. It sets minimum standards for safety, health, amenity, and sustainability.

- BMF (Building Ministers’ Forum): The group of state, territory, and federal ministers that commissioned the Shergold–Weir report.

- ABCB (Australian Building Codes Board): The body that develops and maintains the NCC.

- CPD (Continuing Professional Development): Training hours professionals must complete each year to stay current with building codes and standards.

- Performance Solution: An alternative method of meeting the NCC that isn’t the “default recipe.” It must still prove compliance through testing, modelling, or expert review.

- Deemed-to-Satisfy (DTS) Provisions: The “ready-made recipes” in the NCC. Follow them and you’ve automatically met compliance.

- Private Certifier/Surveyor: An independent professional who checks whether building work complies with the NCC and approves it. In some states, they replace or work alongside council inspectors.

- Occupancy Certificate (or Certificate of Classification): The formal approval that says your building is safe to occupy.

- Third-Party Review: An independent check (often by another engineer or specialist) to confirm a design or performance solution meets the NCC.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Is the NCC changing because of this report?

No. The Shergold–Weir report focused on how the code is enforced and applied, not on rewriting the rules themselves. The NCC still sets the same performance requirements—it’s the compliance and enforcement processes that are being strengthened.

2. Do these recommendations apply to my new home?

Yes. While some reforms are aimed more at apartments and large buildings, many apply directly to houses—especially better documentation, staged inspections, product compliance, and surveyor independence.

3. What should I ask a private building surveyor before hiring them?

Ask three things:

- Do you have a current conflict-of-interest declaration?

- Which code of conduct are you bound by?

- What is your stage-by-stage inspection plan for my project?

4. How do performance solutions affect me?

Performance solutions are allowed, but they must be backed by clear documentation and independent review. Don’t accept “trust me” as an answer—ask for proof of compliance.

5. Will my home be inspected more often under these reforms?

That’s the goal. The report recommends mandatory on-site inspections for all building work, not just selective checks. For apartments, it also means fire safety systems must be tested and certified before occupation.

6. What’s a building manual, and do I get one?

Building manuals are recommended for apartments and larger buildings. They contain as-builts, fire safety details, and maintenance instructions. For houses, you won’t get a formal manual—but you can (and should) create your own version by compiling all approvals, certificates, and warranties.

7. How quickly will changes happen?

The report suggested a three-year rollout, with each state reporting progress annually. That means some reforms may already be in place, while others are still in development depending on where you live.

8. Does this stop dodgy building products being used?

Not overnight. The report pushed for compulsory product certification for high-risk products, but until that’s fully in place, it’s up to you to ask for evidence of conformity for the materials going into your home.

9. Is private certification going away?

No. The report keeps the private certifier model but recommends stricter guardrails, codes of conduct, and enforcement powers to make sure they act independently.

10. How do I know which recommendations matter most for me?

It depends on your building class. For houses, focus on documentation, inspections, surveyor independence, and product compliance. For apartments, add fire authority engagement, building manuals, and fire system certification to your checklist.

Further Reading